An aerial view of Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL) oilsands mining operation near Fort McKay. RYAN JACKSON / Edmonton Journal

From a climate perspective, oil sands are a carbon catastrophe.

Extracting crude from Canada’s oil sands is more complicated than tapping into a gusher of oil. Instead, oil companies must steam or mine a sticky, tar-like substance called bitumen out of the ground. For deep deposits, miners sink deep shafts to access deposits and force steam underground. In surface extraction, companies excavate massive open pits to process the oil-laden earth.

The energy required to pull this oil out of the ground and process it is enormous. It takes three to five units of energy from natural gas to produce one unit of energy from oil sands.

That makes it one of the most carbon-intensive fuels on the planet. Burning even a fraction of the 165.4 billion barrels in Alberta’s estimated reserves would likely raise temperatures far beyond the 1.5C rise scientists believe is needed to avoid more dangerous warming.

The oil price collapse could be temporary. Or it could be the start of a long-term decline for one of the most carbon-intensive fuels on the planet.

Is this end of the oil sands?

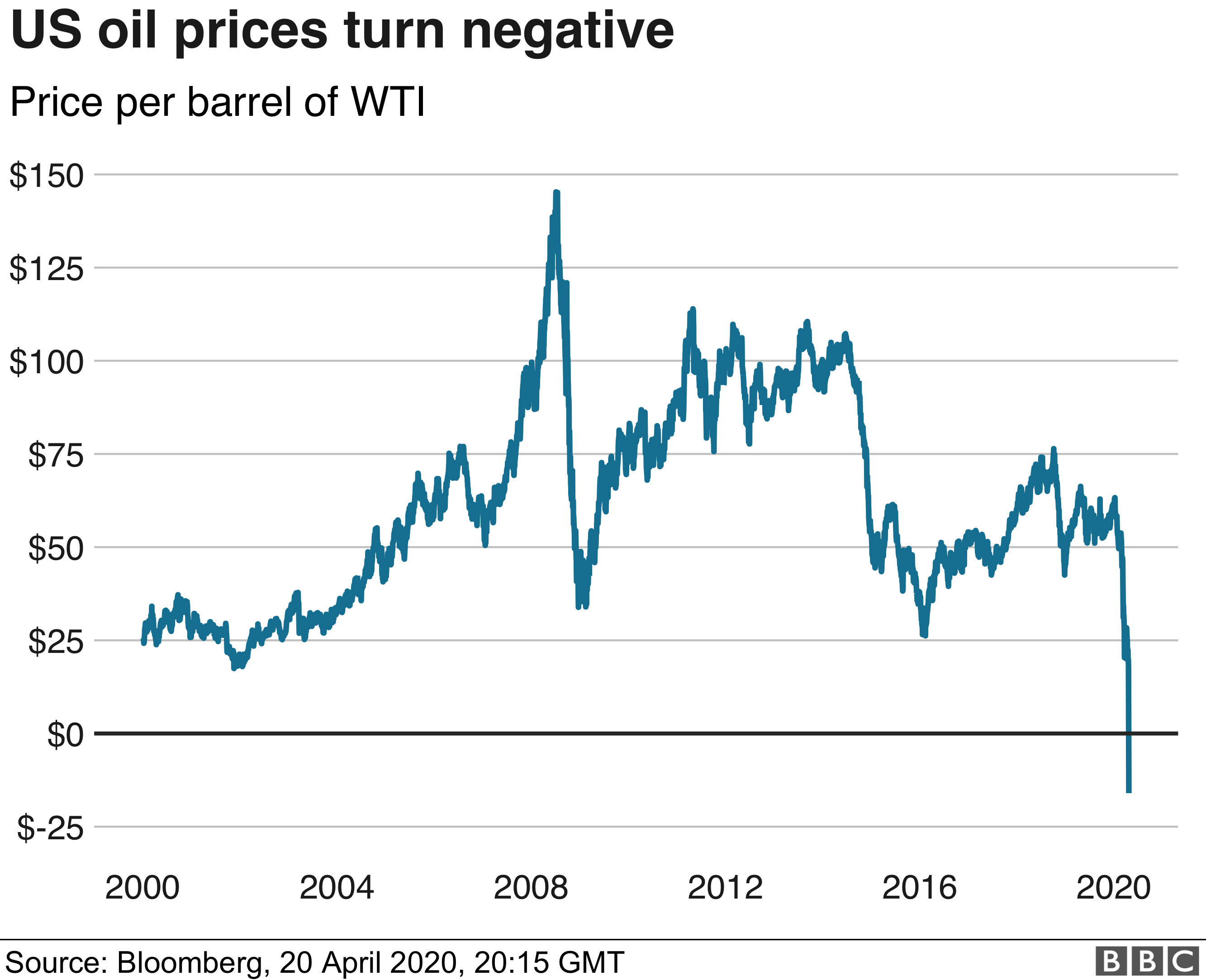

Globally, the Covid-19 pandemic has sent oil prices (and demand) to unprecedented lows. For everyone but the lowest-cost oil producers, particularly in Russia and Saudi Arabia, today’s oil price is unsustainable.

On April 20, a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil was selling in the US market for -$36.20 a barrel. American traders were paying people to take oil off their hands as storage space ran out, and Canadian crude spiraled downwards. That’s never happened before.

While Canada’s oil prices didn’t quite plumb those depths, the industry is in even worse shape. Crude from Canada’s oil sands is sold as the Western Canadian Select (WCS) grade. Its price is calculated as a monthly average of WTI daily prices, usually at a 20% discount (or more) because it’s far more expensive to extract and transport.

While WTI has recovered to around $15, the price difference between the grades is even larger as Canadian crude bottoms out. Future contracts for crude from Canada’s oil sands are now trading at $7 per barrel (April 27) falling from $35/bbl in February. Firms reliant on the region have seen share prices cut in half.

The Canadian crude industry is getting more efficient, but no one can make money selling at that price. In the last five years, oil sands firms have fought to compete by slashing costs by about one-third. That’s brought the industry’s break-even prices down from $100 per barrel in 2014 to between $45 to $50 today (although some facilities are more efficient).

Stemming the losses won’t be as simple as slowing production. A halt in mining can permanently damage underground reservoirs if heat and pressure are not maintained. If companies do restart production, it may take months to reach previous levels (unlike conventional oil wells). Since most costs must be paid whether companies are pumping or not, it’s often cheaper to run at a loss for months or even a year.

ConocoPhillips, Husky Energy, Cenovus Energy, Athabasca, Hangingstone, and others have all voluntarily slashed production. Steeper cuts of more than 25% of production are on the horizon. The research firm GlobalData estimates crude oil production in Canada will fall at least 600,000 barrels per day this year, and continue to fall if prices don’t bounce back.

Thomas Liles, an analyst with research firm Rystad Energy, expects the industry to scale back spending by more than 40%, the lowest point in two decades, but resume extracting as prices recover through 2022. Projects deferred this year will be moved to the coming years as WTI prices recover to $30 or $40 per barrel, estimates Liles.

Meanwhile, capital may be slowly drying up. Trains and a very limited set of pipelines carry oil sands crude to refineries. The massive proposed Keystone XL pipeline, now years behind schedule, was blocked by the Obama Administration, local communities, Native American tribes, and others worried the new channel to transport billions of barrels of oil threatens their lives and lands. The longer the pipeline’s viability remains in question, the less attractive the oil sands will be. HSBC, BlackRock, and others have already said they will move their investments or financial offerings away from positions in Alberta’s oil sands. And Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, Sweden’s largest pension fund, BNP Paribas Group, Société Générale of France divested from the company building Keystone XL.

Those concerns may slow, but not stop oil sands development. This month, the provincial government in Alberta stepped in with a $5 billion package of financing and loan guarantees for Keystone XL, and the Trump Administration granted permission to resume pipeline construction during the pandemic (a court order from a federal judge halted this again). Smaller pipelines and railcars can also take oil sands crude to market. And although oil prices remain at rock bottom today, a modest global recovery could push them back up to levels that make at least some of Canada’s oil sands profitable.

Only a carbon price, or regulation, is likely to keep most of the oil sands in the ground. That might come after 2025, according to a study commissioned by Principles for Responsible Investment, a UN-supported investor group with $86 trillion in assets. Last year, it warned of an “Inevitable Policy Response” by mid-decade, a massive global correction that devalues carbon-intensive assets and industries. The research predicted a 3.1% devaluation, equivalent to $1.6 trillion to $2.3 trillion by 2025. The fossil fuel sector will be hit hardest.

But so far, Liles says, climate concerns are not part of oil sands producers’ calculus. “I wouldn’t say carbon is something we’ve seen factored into long-term production goals,” he says. “The default thinking is continued growth and lower upstream emissions where possible. I’m not sure anyone is thinking on a global scale.” SOURCE