Further down the aisle, recycling bins stood next to a collection of striped t-shirts and dresses.

Like its other fast fashion rivals, H&M’s core business model is fueled by low prices, rapid consumption and fast-changing trends — all of which are in direct tension with its sustainability mission. The global fashion industry generates a huge amount of waste – one full garbage truck of clothes is burned or sent to a landfill every second, according to the a report by the

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a leading non-profit working to improve the industry’s sustainability record.

When a shirt costs $5, it’s quickly seen as disposable. We are more likely to dispose of cheaper, mass-produced clothes than more expensive items, according to a

2009 study into consumer habits.

H&M is well aware of the problem. The company’s Sustainability Engagement Manager Hendrik Alpen admitted the fast fashion industry is struggling to balance its climate commitment with its desire to meet consumer demands.

“It’s not exactly rocket science, if you look at how the global population will develop, by 2040, we might be 9 billion people. That is of course great from the perspective of having more potential customers,” Alpen told CNN Business. “But if we look at the planetary boundaries … the equation is not working out.”

How clothes are harming the planet

Collectively, the global fashion industry produces nearly 4 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, or 8.1% of the world total, according to

Quantis, a climate consultancy that analyzes the fashion industry’s environmental impact. That calculation includes the

seven life stages of a garment, beginning with creating the fibers used to make it — by growing cotton, for example — to assembling the clothing and eventually, transporting and selling it. The estimates consider both apparel and footwear.

When you’re standing in a mall or shopping online and ready to click “buy,” it’s hard to fathom the global consequences of individual purchases. But consider the impact of a single cotton t-shirt or a pair of jeans as examples.

The process of making one cotton t-shirt emits about 5 kilograms of carbon dioxide — around the amount produced during a 12-mile car drive. It also uses as much as 1,750 liters of water. That’s in part because cotton is a water-guzzling crop. Inefficient irrigation, as well as the bleaching and dying process, add to the water usage, Quantis told CNN Business.

Producing a pair of jeans consumes even more water — around 3,000 liters — due to the dyeing and bleaching involved, according to calculations by Quantis. Making a single pair of jeans emits around 20 kg of CO2, the same amount produced during a

49-mile car journey.

There are more sustainable ways to grow cotton that include relying mainly on rainwater, rotating crops to preserve soil quality and limiting the use of pesticides. However, sustainable cotton remains a niche product, comprising only about 15% of the 2017 global total, according to the

CottonUp initiative.

In 2017, the fashion industry devoured around

79 billion cubic meters of water, enough to fill nearly 32 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. And it’s only expected to get worse. The Global Fashion Agenda and

Boston Consulting Group expect the fashion industry’s water usage will increase another 50% by 2030.

That’s a threat, they warn, particularly to cotton-producing countries, which are quickly running out of water. Researchers at the Twente Water Centre at the University of Twente in the Netherlands say

4 billion people experience severe water scarcity for at least one month each year. Nearly half of those people live in India and China, the world’s top two cotton producers.

In Central Asia, another major cotton region, cotton farming is partly responsible for

drying up the Aral Sea, once one of the four largest freshwater lakes in the world.

The Aral Sea, located on the border between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was once the world’s fourth largest freshwater lake. It shrunk to just 10% of its original size by 2000, and continued drying up since.

It doesn’t end with the production. Washing clothes can also have a detrimental effect on the environment, especially because of synthetic materials like polyester that contain plastic fibers. After frequent washes, those fibers break down into microplastics, which can make their way to oceans and harm marine wildlife.

“60% of materials used by the industry are plastic fibers [and] the equivalent of 50 billion plastic bottles are leaked into the ocean through garment wash every year,” said Francois Souchet, who leads the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s

Make Fashion Circular program which brings together all the key players to create more sustainable fashion.

Denim manufacturer Levi Strauss is on a mission to change this.

For years the company has been

encouraging its customers to reduce the number of times they wash their jeans. A 2013 report commissioned by the company revealed that consumer care was responsible for

23% of water used in the life cycle of its jeans.

Levi’s also found a way to create its signature faded denim, by using

just a thimble of water and ozone gas instead of the traditional method, which can use up to 42 liters of water.

The company uses stones instead of water to achieve the “worn-in” look. This technique has reduced the volume of water used in garment finishing by 96% since 2011, the company says.

Sustainability comes at a high price

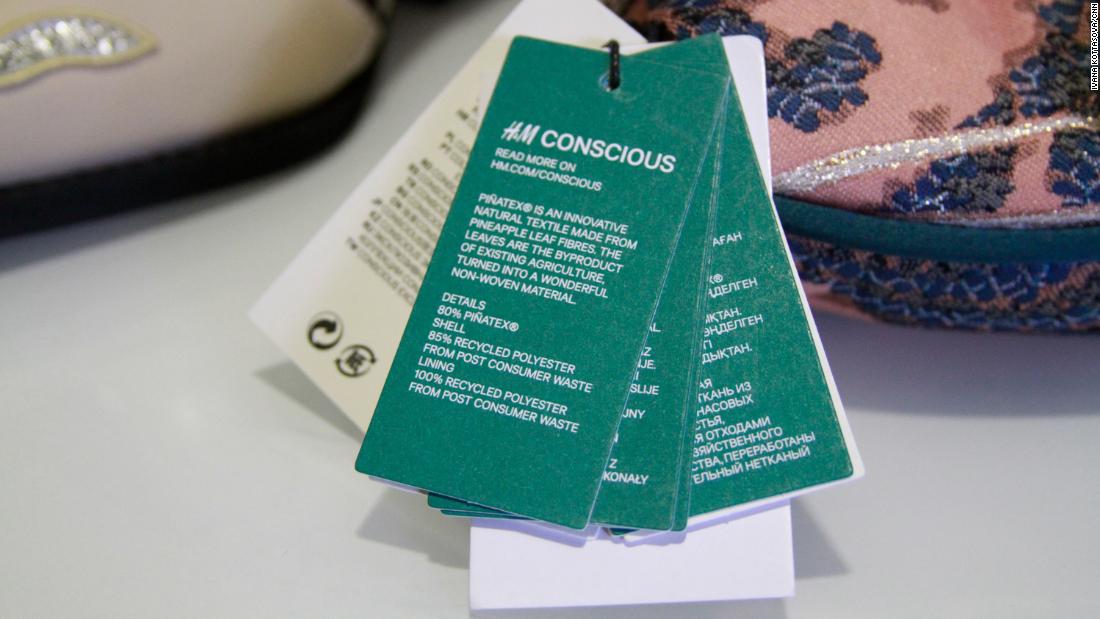

H&M launched its Conscious Collection in 2010. To qualify for a “Conscious” label, clothes must contain at least 50% sustainable materials, such as organic cotton or recycled polyester, according to the H&M website.

The company was accused of “greenwashing” consumers by being vague about the collection’s sustainability credentials. Last summer, the Norwegian Consumer Authority sent a letter to H&M, accusing the company of misleading consumers with overly general sustainability claims associated with its Conscious Collection. The NCA told CNN Business that the information on H&M’s website did not specify the amount of recycled material used in each garment.

“We think this is information that the consumer should have available as the clothing is marketed as recycled,” said Elisabeth Lier Haugseth, NCA director general. “You should know if this means 2% of the clothing material or 50%.”

When asked about this, Alpen, the H&M sustainability manager, said the company would take the criticism and learn to “communicate that extra value” to consumers.

The Conscious Collection includes items like a vegan pink jacket made from Piñatex, a leather-like material made out of pineapple waste and recycled polyester rather than animal hides.

The catch: it originally cost $299.

That price tag, which stands out in a sea of otherwise super-cheap clothes, illustrates a hard truth; although H&M is making more of an effort to talk about climate change, it’s hard to scale up sustainable practices and still keep prices low.

Developed by leather goods specialist Carmen Hijosa, Piñatex has become a sought-after material. Hijosa has teamed up with a number of luxury designers, including

Hugo Boss,

Trussardi and

Edun, in addition to her H&M collaboration. She hopes to scale her company so Piñatex can eventually supply more apparel-makers with a leather alternative at a lower price point. For now, she acknowledges the $299 H&M jacket is probably out of reach for many consumers.

But she also told CNN Business that it’s up to shoppers, too, to play their part – by purchasing fewer and longer-lasting goods.

“We consumers have a lot of power. I think we all know we don’t need 20 t-shirts,” she said. “Maybe it’s better to pay a little bit more and have two t-shirts.”

“I think we are much, much more aware,” she added. “People stop for five seconds and think: ‘if I buy this, it’s going to be a waste in six months time, if I buy this, it’s going to last longer, it [costs] more, but I am going to use it more’.”

Throwaway fashion

Fast fashion companies produce billions of garments each year to provide their consumers with the latest trends. Critics, ranging from Greenpeace to the UK Parliament, say such mass production promotes the idea that clothes are disposable and encourages excessive waste.

Over half of fast fashion items are thrown away in under a year, according to estimates by management

consultancy giant McKinsey & Company.

The problem is becoming apparent. In its 2019 “

Fixing Fashion” report, the UK’s House of Commons’ environmental audit committee proposed that the government introduce a fast fashion tax to combat consumers’ disposable mindset. The inquiry’s tagline: “Fashion: it shouldn’t cost the Earth.”

The committee’s overarching message was straight forward: People need to rethink the way they dress by buying fewer but higher quality items that will last.

“Isn’t the real problem with the fast fashion industry that if you are selling stuff at £5 people aren’t going to treat it with any respect and at the end of its life it’s going to go in the bin?” asked Mary Creagh, the parliamentarian who chaired the committee.

The proposed tax was tiny, just one pence (or about 1 US cent) per item. The lawmakers wanted to use the revenue to stop clothes from going to a landfill.

And ultimately the government rejected the idea, saying it wanted to focus on eliminating single-use plastic first.

Most used clothing isn’t recycled

In a bid to play its part, H&M launched a recycling program in 2012, allowing customers to exchange unwanted clothes for discount vouchers.

H&M’s latest sustainability report stated that of the used garments it collected, 50% to 60% were sorted for rewear or reuse. About 35% to 45% were recycled to become non-fashion products like cleaning cloths or insulation materials or made into new textile fibers. The remaining 3% to 7% that could not be recycled were burnt for energy production. 0% ends up in landfill.

The company aims to operate a 100% circular business model by 2030, which means ensuring that there is “no end of life [for materials] but creating a closed loop where everything is used as long and as often as possible and ultimately recycled,” Alpen said.

But some critics call this yet another example of greenwashing on the part of the company.

Orsola de Castro, a designer and a co-founder of Fashion Revolution, a non-profit global movement, said that the industry’s focus on circularity is a sign that the biggest companies are “hell-bent on continuing” with their current business model.

“These brands know very well that just throwing a couple of millions at some experimental circularity [project] was not going to solve the problem, but it was going to give them the opportunity to say ‘in the future, we can produce as much we want, you will be able to buy as much as you want, because ultimately, we will recycle everything’, but that is absolutely not true,” she said.

The future the companies talk about, she said, is so far away, it won’t make a difference any time soon. “We need to usher in a different behaviour by changing buying habits in the meantime, and that to me is slowing down,” she added.

H&M Group says it collected more than

29,005 metric tons of unwanted clothing in 2019, but admits that for many types of textiles, viable recycling solutions either do not exist or are not commercially available at scale.

Worldwide as of 2015, 73% of clothes ended up in landfills or incinerators because they cannot be recycled, according to the

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a non-profit working to improve the industry’s sustainability record.

The main challenge is a lack of recycling infrastructure for textiles. Current technology only allows less than 1% of clothing to be recycled into new apparel, Francois Souchet, who leads the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Make Fashion Circular program, told CNN Business.

He said the fashion industry should design clothes with end of use in mind by integrating recyclable materials, such as lyocell, a fiber made from biodegradable wood pulp.

“The products are not designed to be turned into new [items] or refreshed in style…the materials that are used mean you cannot economically recycle clothes,” he added.

Most experts and fashion companies acknowledge the task ahead is huge and will require a multitude of solutions and technology that is not yet available.

“I don’t think there is a truly sustainable fashion business, but looking at the rest of the industry today, I can say very confidently that H&M is one of the most sustainable options out there,” Alpen said.