Solar panels on a roof in California. PHOTOGRAPHER: JOSEPH DESANTIS/GETTY IMAGES

Planet of the Humans has stirred the resentment of many a climate crusader. Yesterday, the chair of the Sierra Club California Energy and Climate Committee instructed committee members (I am one) not to “watch or promote” Planet of the Humans. Today, climate scientists called for the film’s suppression. Enticed by such parental warnings, like an aroused teenager, I just had to watch it.

The film, produced by left-wing film idol Michael Moore, appears to expose and debunk current environmental initiatives for “100% renewable cities” in the United States. Sierra Club activists view the film as undermining climate action on Earth Day. But as the creator of Community Choice Aggregation, which accounts for 67 of 71 U.S. cities that have actually achieved 100% renewable electricity as of 2020, I feel compelled to speak up.

There is some truth to this film, hidden behind a multitude of glaring falsehoods. It is important to explore what the film gets right. As climate activists in the era of climate disruption, we must be clear about what our carbon reduction polices are actually going to achieve, as we push local communities around the world to implement Green New Deal programs, Paris Agreement targets, climate mobilizations, and renewable energy initiatives. Let us not get caught up, after all, in lies created not by environmentalists, but by utilities and governments that have propagated them. They are not our lies, and therefore we need not keep them, but renounce them when clearer, bolder, more concerted actions are required to meet the United Nations ten year horizon for “worldwide energy transformation to avert irreversible ecological damage to the planet.”

The main message of Planet of the Humans is that renewable energy and electric vehicles and other technologies cannot stop climate change, but merely introduce new forms of pollution and environmental destruction. The film’s sense of hopelessness is mesmerizing. Reviewing the progress of renewable energy in recent years, film director Jeff Gibbs sniffs out contradictions and presents them in a kind of cascading epiphany of juvenile disillusionment. Wind farms’ intermittency requires massive natural gas power plants. Solar farms destroy the desert. Lithium ion batteries involve new forms of sea-bed mining for rare earth metals. Each solution to climate change creates a new problem, to the extent that it merely repowers the same economy, and the same civil society. Conclusion: humanity is destructive.

Yet, between these layers of accusation lie some very, very important and salient truths. Planet of the Humans presents harsh realities about our world, mixing up cause and effect, technology and policy. We must unpack these conflations.

In doing so, we find dominant neoliberal currents, often unconscious, at the heart of the environmental movement that profoundly undermine its impactfulness. By continuing to gloss them over in the era of Trump, mainstream environmental organizations are in fact sowing the seeds of counterrevolution. I know this, because I come up against it every day in the very green energy movements I have started, led and in some cases lost to neoliberals who don’t even know they were neoliberals, whose approach to greenhouse gas reduction is to promote the technological fixes and market solutions that are the idols of capitalism, presenting the illusion that solving climate crisis is as simple as a new line of products to consume.

Gibbs and Moore’s critiques are real, but they oversimplify the problem they describe as an existential crisis with no exit. This delivers them into the pessimistic catch-basin of “overpopulation” theory: we simply have to die to solve climate change. This leathery insight is indeed the conclusion of Planet of the Humans.

However, if you look at infrared satellite images of global greenhouse gas emissions, you will quickly observe physical sources do not correspond to high population areas, but to modern economies: that is, machines. Automobiles, power plants and heating fuels cause climate change, not people. Let us look at China as an example. Before it was “opened” by the Clinton Administration to investment from the West, it had very low carbon emissions. In just a couple of decades, its industrial modernization has made it the epicenter of climate catastrophe. Constant driving, overconsumption, and parasitic capitalism have caused climate change. Therefore, to stop climate change, we must alter modernity, not blame people or wallow in misanthropy. Specifically, we must remove the growth imperative from energy. To do this, a climate mobilization strategy must wean itself from neoliberal dependency upon incumbent energy corporations and financiers who require consumption growth in their business models in order to profit from its development.

Oddly, Planet of the Humans reproduces the fictions of neoliberal environmentalism, failing to get to the truth by reifying technology as the problem. This is much as the environmental movement has reified technology as the solution. We must understand that the failures in renewable energy result from policy, regulation, and market design, not technology. By merely focusing on the unwanted attributes of the technological manufacture of solar panels, electric vehicles and wind farms, the film makers betray a naivety about the real reason we are failing.

Meanwhile, environmentalists criticize Planet of the Humans with a similar naivety, citing the film’s “lies” and “attacks” on what they consider to be promising progress. Where their critique fails is in seeing any progress made as close to remotely adequate relative to the scale of the climate crisis, and the hyper-speed by which we must attack it.

Planet of the Humans states that the 100% clean energy movement led by Sierra Club with a $80M donation by Michael Bloomberg has created a renewable front for natural gas. This would seem to imply a nefarious conspiracy, but in fact it merely reflects the state of things, to which Sierra Club and other leading climate warriors have wearily adapted themselves: a state-sanctioned system of salutary fictions. Because environmentalist leaders, facing limited political options, blur the lines between what is real, and what is symbolic with respect to “clean” energy, they leave themselves open to charges of falsehood.

Indeed, the renewable energy industry is guilty of the propagation of convenient fictions. Since the 1990’s, renewable energy policy has remained inside a neoliberal envelope, widely adopted by state governments and environmental champions of such policies. These policies are the holy grail of renewable energy in 2020, and they include: Renewable Energy Certificates, Carbon Credits, Greening the Grid, Net Energy Metering, and Feed-in Tariffs. Together, these fictions are a startup strategy to begin something new, not an end game strategy to transform energy.

The first fiction is embracing Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) as real, when they are not. The 100% renewable movement is certainly guilty of this, because it does not distinguish between physical and symbolic actions. A Renewable Energy Certificate is a legal invention, not energy: yet the legal invention authorizes its purchaser to call it renewable energy. This is confusing because it is untrue. REC state laws in the most pro-renewables states allow a seller of coal-fired power to claim that his product is 100% renewable, because he purchases RECs from out-of-state wind farms such as in Texas. This is referred to as “mitigation” under state laws throughout the United States and blurred into legal definitions of “green power.” This thinking follows a logic that the environmental movement has been trained to accept, from day one of electric industry restructuring in the early 1990’s – a market logic. RECs are a financial, not a physical, transaction and so no, we are not building renewable energy, and yes, the power plants generating the power you are purchasing as 100% renewable are in fact coal-fired. The rationale is that the RECs we have purchased will create an “incentive” upstream in the market to become greener.

The fiction of Carbon Credits is that laws allow corporations causing massive amounts of carbon pollution to claim they are 100% carbon neutral by purchasing them. Again, the same claim is made that the purchase of such credits sends an “incentive” to the market to reduce carbon.

The use of “incentives” pervades renewable energy and carbon policy, and profoundly undermines the ability of people to be able to differentiate between the real and the unreal. Today, the environmentalist establishment is guilty of propagating unreal policies in order to galvanize public support of oversimplified, financialized, superficial paths to carbon reduction. Given the mounting urgency of bringing about dramatic carbon reductions to avoid passing the threshold of being able to avert climate catastrophe, movements for climate mobilization must take notice of decades-old incentive schemes that were never designed to do anything but stimulate infant green industries, not physically transform and decarbonize the energy system.

A third fiction is the notion that we can green the grid. The effect of this approach is the equivalent to pissing into the ocean, a growing ocean, of global demand. Adding wind farms and solar farms to the grid is caught in a permanent dilution where, as Planet of the Humans points out, grids require solar farms and wind farms that generate power 20-30% of the time backfill with gas plants to generate 70-80% of the time. This gives the lie to “economies of scale.” As long as renewable energy is not local, meaning sited at the location of use, and indeed smaller, this intermittency will continue to require significant fossil fuel in tandem, and – as the film rightly points out – natural gas is not clean energy: quite the contrary, it is as harmful to the climate as coal.

This brings us to the final, least understood fiction of all. Virtually all on-grid solar systems in the world today are wired, used and paid for on the same fictional principle as RECs, Carbon Credits and the green grid: not to reduce the need for grid power in a building, but to sell power back to the grid. Net Energy Metering (NEM) and Feed-in Tariffs (FIT) are guilty of deliberately avoiding reductions in grid energy demand, and in maximizing energy transactions and grid use, rather than reducing demand and grid use. NEM and FIT render the carbon benefits of solar superficial, and drive up the need for more grid investment, resulting in more fossil fuel use.

These failings of renewable energy are not the result of solar or wind technology and its waste: but of how they are designed, how owned, and controlled. Planet of the Humans makes the fatal mistake of correctly identifying some of the cracks in the edifice of carbon reduction, but widely misses the mark of causality. Their insistence on a kind of sentimental asceticism, for example that solar panel manufacturing requires energy and metals, is a silly, millimeter-deep insight. That windmills are made of steel and concrete is an utterly foolish objection, reflecting an absence of perspective or proportionality, and an eco-Manichean view of all economic activity as dirty and evil. It is critical to parse the fact from the fiction here in order to avoid the existentialist, misanthropic malaise into which this film, in the end, settles, while also agreeing that the alarm raised – that conventional, incrementalist solutions are not adequate – is certainly heard. Planet of the Humans’ successful sniffing out of ironies concealed behind legal platitudes is limited by a resignation and pessimism of the death instinct that is antithetical to our survival and sustainability. We must navigate through the Valley of Subtleties that distinguish hypocrisy from irony.

Turning away from technological fetishism, negative or positive, we must turn to politics. Why do all of these neoliberal policies have in common the quality of changing individual human behavior (choosing green) without changing the system (actually decarbonizing)? Because deals were made, and “necessary illusions” endorsed. The energy industry, and state governments under their undue influence adopting renewable energy laws, created them to work that way. Electric utilities did not, and do not, want their profits reduced, their revenue requirements changed, and their business models threatened. State mandates can force consumers to pay money toward a good cause, but not force utilities to reduce corporate profits. So it was therefore arranged to measure progress in (“other people’s”) dollars spent rather than carbon cut. It is a classic study in making progress while not rocking the proverbial boat: incrementalism hidden in a message of moral sacrifice.

The good news is that movements are currently underway to change all of these things, but these are not technological movements. They are not led by billionaire geniuses, big foundations nor even most of the “big” environmental NGOs, but by municipal governments and the activists who support them. Importantly, the centralization of renewable energy development, the obsession with maximizing transactions rather than demand reduction (the growth imperative) and its ineffectiveness as a carbon reduction strategy, are valid insights that mainstream environmental leaders and their campaign messages continue to miss.

Decentralization is a critical pathway, with major movement underway across the nation and world, that the film also simply fails to acknowledge at all, as if it didn’t exist. In fact, the community energy movement is underway, led by a different breed of environmentalists. Local installation, pairing local generation with local use, with local investment, neighbor-level sharing and cooperatives, and interoperable use and storage of onsite energy, present widely replicable, proven strategies to actually, physically, and enduringly slash carbon emissions. In fact, of the 100% renewable US cities today, many of them, known as Community Choice Aggregations, are taking just this approach.

The film’s snapshot of green energy is a little old, but so is the propaganda of mainstream environmentalists now (idiotically) calling for Planet of the Humans to be censored from the internet. Community energy programs are focusing on deployments of renewable energy technology to not purchase Renewable Energy Certificates, build green megaprojects or implement Net Energy Metering programs, but to finance and build new local renewable, demand-reducing facilities in the urban core. They are physically building renewable energy, microgrids, urban heat loops, and energy efficiency automation in a way that reduces grid demand rather than merely selling back power to the grid. Not only that: they are focusing on climate equity, customer ownership and sharing, and local job creation, so that the majority, not the select few, can participate in and benefit economically from local renewable energy. These movements, which represent the cutting edge of climate action, are finding ways not merely to add green power to a brown grid, but to physically reduce the need for fossil fuel combustion, and to displace demand for heating and transportation fuels.

None of this is on the radar of Moore’s film, but neither is it clearly distinguished in the minds of mainstream environmental groups that promote 100% clean energy cities. Environmentalists and lawmakers need to learn to get real about carbon reduction if we are to meet the urgent 2030 deadline recently set by the United Nations. We need to get out of startup mode and into endgame mode, that means a radical physical transformation in three years, not ten, to even come anywhere close to reaching the UN targets by 2030. We need clearer paths to radical decarbonization that overcome the glaring contradictions caused by bogus strategies to green the grid, sell renewable energy and carbon credits, and net meter solar. This is a shift from greening to weaning ourselves from the grid: from additionality to subtractionality of carbon, from carbon taxes and fees to energy equity. Planet of the Humans may be wrong on the details, but environmental activists would be remiss to ignore its message and maintain the useless fictions of neoliberal environmental policy in the era of climate crisis. In the final analysis, this film is a needed call to arms for the environmental movement to embrace an End Game scenario for climate action, effective immediately. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.

Paul Fenn is the author of CCA 3.0: Achieving Greenhouse Gas Reduction (2020), co-director of the Local Green New Deal (localgreennewdeal.org), president of Local Power LLC (localpower.com) and co-author of Enlightenment in an Age of Destruction (2018). He lives in Massachusetts.

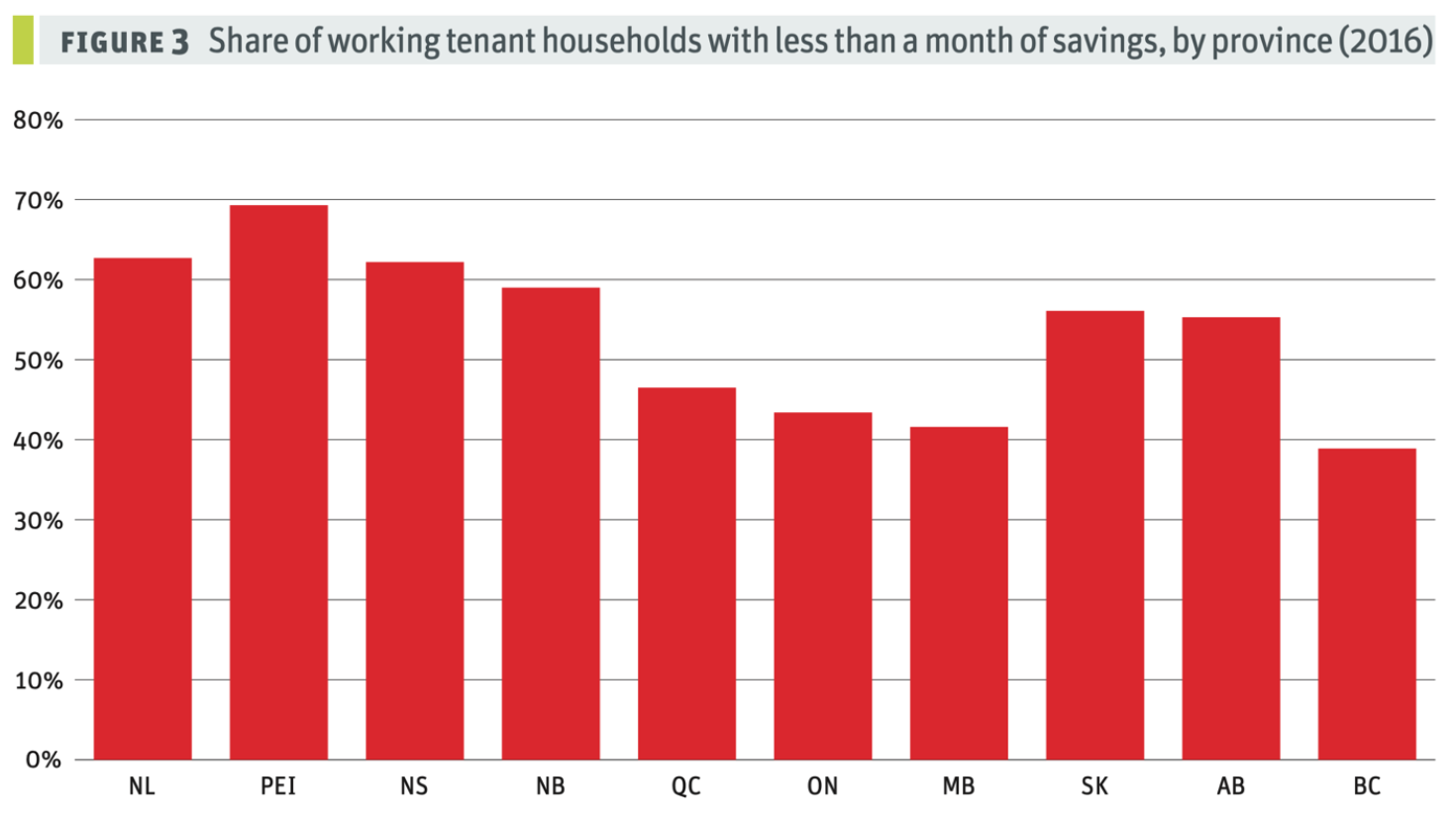

Source: The Rent is Due Soon: Financial Insecurity and COVID-19, Ricardo Tranjan, CCPA, March 2020.

Source: The Rent is Due Soon: Financial Insecurity and COVID-19, Ricardo Tranjan, CCPA, March 2020.

1 comment: