As another new gold mine is proposed in the province, conservation groups are concerned its construction could decimate protected habitat for at-risk species in an area long-renowned for its angling and spawning habitat

A springtime flood along the St. Mary’s River in Nova Scotia. Local conservation groups worry that a proposed new gold mine will threaten the at-risk species that rely on this habitat. Photo: Irwin Barrett

Plans for a new gold mine threaten decades of restorative work on Nova Scotia’s longest river, which provides prime spawning habitat for at-risk wild Atlantic salmon, according to the St. Mary’s River Association.

The organization was founded in 1979 after salmon populations, once attracting famous anglers including Babe Ruth and Michael J. Fox, began to decline.

Since 2014, the association has spent $1.1 million rebuilding riverbanks and spawning habitat pulverized by historic log drives, and just last year received $1.2 million to shield this river from acid rain.

“We look after the river,” said president Scott Beaver, pointing to the fish ladders they’ve built over human obstacles and stocking initiatives to bolster salmon that are now finally returning to spawn.

Rare footage released Wednesday shows a spawning pair of salmon in McKeen Brook, a tributary of the St. Mary’s which Beaver and others in the Nova Scotia conservation community fear will come under a new threat from the proposed Cochrane Hill Gold mine.

Atlantic salmon, an at-risk species, are one of the primary concerns of conservation groups pushing back against a proposed gold mine near Nova Scotia’s St. Mary’s River. Photo: St. Mary’s River Association

The project, proposed by Atlantic Gold (Atlantic Gold was purchased by St Barbara, an Australian gold mining company, last year. St Barbara now runs Atlantic Gold Operations in Nova Scotia), would involve the construction of an open-pit gold mine one kilometre long, half a kilometre wide and a maximum of 170 metres deep alongside the river. In total, the project would involve some 240 hectares (roughly 450 football fields).

According to a project description submitted to Canada’s Impact Assessment Agency, the mine would produce two-million tonnes of gold-bearing ore per year and have a life span of just six years. (St Barbara did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment.)

The company has yet to release an environmental impact assessment for the project as it makes its way through environmental review, which it began in 2018.

Mine proposed at height of river conservation

The Cochrane Hill mine would, as described in the company’s project description, process excavated rock into a gold concentrate which would then be transferred 142 kilometres to Atlantic Gold’s existing Moose River mine, where the gold is extracted.

The Moose River gold mine in Nova Scotia. The company behind this mine is proposing a new project in the province, one conservation groups worry will further endanger at-risk species like the Atlantic salmon. Gold concentrate produced at the Cochrane Hill mine will be transported and further processed at Moose River. Photo: Raymond Plourde

The initial processing at Cochrane Hill would result in tailings ponds on site, contained behind dams perched above the St. Mary’s watershed. Any treated effluent would be discharged into the Cameron Lakes, which drain through McKeens Brook, arguably the most productive spawning habitat on the river, according to Beaver.

In 2018, Beaver met with representatives of the mining company, who described the project plan.

“My life completely changed,” Beaver said of the meeting.

The proposal caused a similar upset for the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, which, since 2006, has constructed a network of protected properties totalling 540 hectares along the St. Mary’s.

A sandbar on the St. Mary’s River in Nova Scotia, a protected area local conservation groups worry is under threat from a proposed gold mine. Photo: Irwin Barrett

The trust — which has a mandate to acquire the most ecologically significant properties throughout Nova Scotia and protect them in perpetuity — has been busy with the banks of the river with its unusual abundance of old-growth and floodplain forests. Ancient hemlocks, maples, oaks and spruce in these rare forest zones provide habitat for a suite of at-risk species.

“This is starting to become a major natural corridor,” Bonnie Sutherland, executive director of the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, told The Narwhal.

“You have habitat connectivity for wildlife, the chance for long-term viability for these amazing floodplain forests, the old growth hemlocks, habitat for endangered turtles and birds and maybe, someday, the Atlantic salmon can make a comeback.”

“It’s pretty ironic that this proposed mine is coming at the height of conservation achievement on this river,” she added.

Spring reflections in an inlet of the St. Mary’s River in Nova Scotia. Photo: Irwin Barrett

Mine requires road through land trust

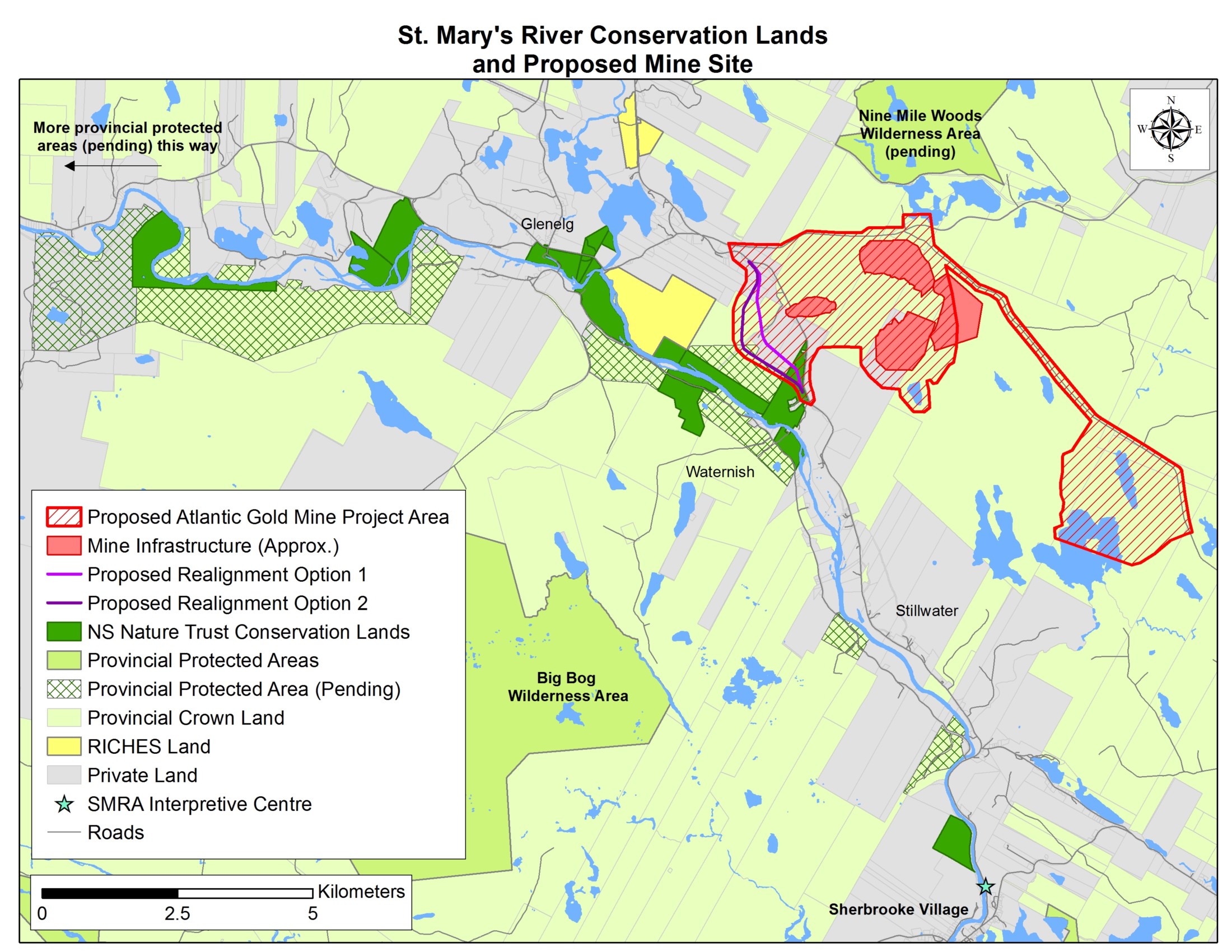

The proposed Cochrane Hill mine would necessitate the realignment of nearby Highway 7, sending it through protected Nova Scotia Nature Trust land.

Doing so would require paving over old-growth hemlocks, disturbing resident wildlife with noise, dust and vibrations, Sutherland said, adding the trust learned about the realignment in a letter from Atlantic Gold.

The nature trust’s mandate makes consent for such road construction impossible, Sutherland said. The road could be forced through, but that would require the provincial government to expropriate trust land under the Mining Act or Highways Act, she said.

Rachel Boomer, spokesperson for the provincial Environment Department, declined to answer specific questions about the possibility of road realignment through trust land.

Boomer said the project is currently undergoing a joint federal-provincial environmental assessment, which will consider “potential impacts to all species, including Atlantic salmon.”

“Once the [environmental assessment] document is submitted, Nova Scotia Environment and the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada will host a joint comment period where members of the public are invited to comment,” Boomer wrote to The Narwhal in an email. “Any member of the public can submit information at that time, and it will be considered in the assessment of the mine project.”

But the environmental review hasn’t relieved the nature trust’s concerns about the potential impacts of the project, or the highway rerouting.

“Expropriation would be wrong on so many levels,” Sutherland said. “This is something you don’t realize is a threat until it looms over you.”

Since 2013, the provincial government has built upon the charitable efforts of the Nova Scotia Nature Trust by announcing some 3,800 additional hectares of protected public land alongside the river in forthcoming provincial parks, wilderness areas and nature reserves, which together with Nova Scotia Nature Trust land covers some 4,300 hectares, enveloping 54 kilometres of St. Mary’s riverbank.

The expropriation of this or any protected land for industrial use could undermine the entire effort, Sutherland said.

One mine in a potential ‘string of pearls’

The Ecology Action Centre is a Halifax-based environmental advocacy charity, which has kept a close watch on Atlantic Gold’s so-called “string of pearls” — four Nova Scotian gold mines intended to open in sequence over the next few years.

The first mine in the string, the Moose River gold mine, is already in operation. Three additional mines — the Beaver Dam project, 15 Mile Stream gold project and Cochrane Hill, itself planned for 2023 — are in the process of federal environmental review.

The area surrounding the proposed gold mine. Map: St. Mary’s River Association

Charlotte Connolly, campaign support officer with the Ecology Action Centre, is quick to differentiate these modern mines from those of Nova Scotia’s past — underground, high-yield mines following gold veins or deposits.

Modern open-pit gold mines operate differently, aiming to extract only small flakes of gold diffused throughout tonnes of rock. Rock is excavated, crushed and treated to leach out gold. The remnants are then deposited in a waste pile and resulting chemical muds are stored in tailings ponds, which remain long after the life of a mine.

“To put a mine here is a terrible idea,” Connolly told The Narwhal.

Nova Scotian gold rush?

Despite participating in efforts to conserve land along St. Mary’s River, the provincial government has been supportive of the mine proposal, offering one per cent royalty rates and a Mineral Resources Development Fund, which aids prospectors and developers alike in their search for gold.

The Mining Association of Nova Scotia has taken to the airwaves of CBC to declare a “gold rush” in the province, suggesting, among other things, that the industry’s high wages could be a solution to the economic woes of rural Nova Scotia, a claim the Ecology Action Centre considers exaggerated because this mine has a five or six year lifespan.

“During gold rushes, everyone loses their minds, only seeing dollar signs,” Charlotte said. “They forget every other important thing in the world.”

Michael Parsons, a geochemist and research scientist with Natural Resources Canada, said that while uranium, zinc and lead do occur naturally in Nova Scotian rock, they don’t tend to appear in mining wastes at very high concentrations.

“The main contaminant of concern at most gold deposits in Nova Scotia is arsenic,” he said, “which occurs naturally in the bedrock around these deposits, and can be concentrated during mining and milling.”

Another concern is mercury. In days gone by, mercury was commonly used in the gold extraction process and is therefore well represented in the historic tailings of Nova Scotia, some of which reside at Cochrane Hill, relegated there by underground gold mines between 1868 and 1928.

If disturbed, this mercury could be another source of environmental contamination, a very real possibility to which Parsons has dedicated significant research.

No open-pit excavation

Following their presentation from Atlantic Gold, Beaver and the board of the St. Mary’s River Association transformed from volunteers to activists: consulting experts on the polluting perils of gold mining, meeting with relevant ministers, MLAs and the premier, organizing protests, erecting signage and hosting public information sessions.

Beaver is heartened by the number of area residents vocally opposing the Cochrane Hill Gold Mine, deeming it too great a risk to the social, economic and ecological values of the river.

Local conservation groups have been organizing protests, erecting signage and hosting public information sessions to raise awareness about the implication of the new gold mine proposal. Photo: St. Mary’s River Association

This collective cry of opposition, however, has focused on the negatives. There has been a great deal of good news on the St. Mary’s River in Beaver’s lifetime, which he decided to showcase with an underwater camera in just the right place, at just the right time.

Saving Salmon is the joint initiative of photographer Nick Hawkins and writer Tom Cheney, collecting stories of Atlantic salmon conservation from across eastern North America, sometimes in words, sometimes in pictures — and now in footage.

The pair accepted Scott’s invitation to visit the St. Mary’s River and joined him for several expeditions in the summer and fall of 2019.

Their reward, aside from a great many photos and clips, were 15 minutes of quality footage of a female salmon on her nest, an exceedingly rare filming opportunity which had thus far eluded the Saving Salmon team.

Beaver has confirmed with both the Atlantic Salmon Federation and Nova Scotia Salmon Association that such footage has never before been captured in the Maritimes, and it was taken, of all places, in McKeens Brook, immediately downstream of where the Cochrane Hill Gold Mine proposes to discharge its treated effluent.

This footage and accompanying photos have been collected and edited into an exhibition which Beaver intends to tour, confronting the espoused profitability of the Cochrane Hill Gold Mine with the resurgence of the St. Mary’s Salmon. The footage alone was launched during a press conference Feb. 12 in downtown Halifax.

“If they push a mine through to the St. Mary’s, there’s no place in Nova Scotia, in my mind, that can be protected from mining,” he said. “The St. Mary’s is the sacred spot.”

The St. Mary’s River in Nova Scotia is considered important habitat for many species, both in and out of the water. Photo: Irwin Barrett

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/J4YHIQO2ANDYLJLAP3JVN7ZKCA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/WH5A7PZJ55ER3F2RR4EYWZ5V2I.jpg)