A future of reconciliation is now squandered along with our billions propping up LNG.

Protecting extraction, once again: The scene last year as heavily armed RCMP officers shut down Indigenous checkpoints blocking a natural gas pipeline on Wet’suwet’en land. Photo by Michael Toledano.

It is the job of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners.

— Albert Camus

On Thursday, the RCMP and the Canadian state came to a moral crossroads on a snowy country road and looked briefly down a pathway to reconciliation. Then it said, “Fuck It.”

A highly militarized police presence once again used force against Wet’suwet’en protestors blocking the construction of a $6.6-billion methane pipeline needed to feed a grossly uneconomic $40-billion liquefied natural gas project.

In so doing the police made a mockery of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

It is not a complicated document. As criminologist Jeff Monaghan notes, the declaration expects “that conflicts like this will not be resolved violently or militarily but with negotiated solutions. The document directs us to do peaceful negotiated solutions that respect everyone’s rights, and equally.”

That didn’t happen.

As reliable agents of the Canadian state and defenders of resource extraction, the RCMP let it be known that the Trudeau government puts highly subsidized methane projects ahead of reconciliation and UN declarations.

Let’s be clear: in Canada, low-priced natural gas matters more than unresolved land claims.

By implication the government also told the nation that it puts uneconomic LNG projects ahead of climate change, given that serious methane leaks from the shale gas industry are now accelerating that chaos.

It, too, advances LNG ahead of the destruction of the arable lands and First Nations treaty rights in Peace River.

In that precious part of B.C., the shale gas industry continues to frack, industrialize and fragment that landscape with impunity, because only rural people live there, after all.

The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation are not asking for much: they want Indigenous rights and title respected and acknowledged by the B.C. and Canadian governments.

The chiefs tried to negotiate with the B.C. government over the recent enforcement of a court injunction but got nowhere with Premier John Horgan.

The recent negotiations predictably failed for an obvious reason: the B.C. government has become a salesman for LNG at home and abroad.

The shale gas industry has secured better representation in the B.C. government than ordinary citizens who actually pay taxes.

But what about the 20 First Nations that have signed on to the project, you might ask?

Yes, they signed and the negotiations were colonial. It was sign or get nothing. Many nations signed under severe constraints. Nor were they presented with economic alternatives.

As legal scholar and expert in Indigenous rights Dayna Scott has noted, Indigenous leaders are faced with a “false choice. They’re being asked to choose whether or not they want to sign a deal and get some benefits for their people for a pipeline that’s going to go through whether or not they agree to it.”

Now consider the position of Hereditary Chief Na’Moks (John Ridsdale). He is not willing to settle for mutual benefit agreements or the modern equivalent of beads and trinkets:

“They wanted access to the land, and we said you’re not getting access, you’ll never get approval, not from the hereditary chiefs and not from our people.” A colonial mind, however, can’t fathom such arguments, because it still refuses to come to terms with the nation’s dirty past.

For the most part Canadians remain an arrogant mining people with little regard for the truths of our colonial history. Most still think we have nothing to acknowledge, let alone make amends for.

These deniers or doubters should read the indomitable Bev Sellars, former chief and councillor of the Xat’sull (Soda Creek) First Nation in Williams Lake. Her searing book, Price Paid, presents the issue of reconciliation in a clear and telling metaphor.

Imagine you owned a nice home. Then you graciously shared it with a bunch of white guests from across the seas. Without even saying thanks, these guests took over more and more rooms in the house. Soon they imposed their own laws and even banned the owner’s original customs. Eventually the invaders kicked out the original owners and left them to die.

Until every Canadian can visualize that colonial abuse, until all of us can feel that in our guts, there will be no reconciliation in this country.

Those still unconvinced by Sellars’ metaphor should pick up James Daschuk’s brilliant Clearing the Plains.

We all know that the American government thought they could murder Indians into submission. The Canadian government took a different approach: it pursued a policy of planned relocation, starvation and disease. Indian agents stole funds and raped Indigenous women. Anyone who resisted was hanged. Then came residential schools.

The Canadian state’s willingness to ignore reconciliation is even more galling when you consider its colonial defence of the preposterous economics of LNG and fracked gas in northern B.C.

In Canada, LNG development has become an absurd Soviet engine that ignores costs and environmental damages.

But being Canadian, it drapes itself with the plastic word “responsible.”

“Responsible” subsidies for the foreign-funded LNG industry now include low royalties; nearly $1 billion worth of royalty credits; discounted electricity prices; reduced corporate income taxes; free water for fracking; reduced carbon taxes and the deferral of provincial sales taxes during construction. The Canadian government even invested $275 million in LNG Canada!

These subsidies, however, still can’t make LNG economic. In 2018 the Canadian Energy Research Institute examined the economics of LNG.

It concluded that Western Canada LNG would be $1 to $3 more expensive than the current spot price in Japan of $8 per million (BTU) and needed more subsidies and tax credits.

CERI then calculated what the LNG industry would need in terms of future prices to remain economically viable: a market price of $8.99 per million BTU or higher in Asia to break even. Or an oil price of approximately $80 or higher to break even under long-term LNG contracts.

Those conditions don’t exist and show no signs of coming into being.

A global LNG supply glut has collapsed prices in Asia to as low as $5.5 per million BTU in Japan and India. Analysts say the glut could last years.

Meanwhile oil prices, which influence LNG pricing, remain in the doldrums.

Unless the Canadian and B.C. governments are prepared to give away LNG, neither Coastal GasLink nor LNG Canada are economic at this point in time.

These appalling economics explain why Chevron pulled out of the Kitimat LNG project last fall. At the same time, Chevron wrote off $11 billion in underperforming shale gas assets in Appalachia due to low prices and overproduction.

Throughout North America’s oil patch, the shale boom has collapsed as more companies go bankrupt and investors refuse to loan more money to companies whose costs exceed their revenue.

Given the volatility of commodity prices, reconciliation should come first.

And let’s not strut like peacocks and talk about the rule of law as Horgan has done.

In Alberta, oil and gas companies now break the law every day. They owe $172 million in taxes to rural municipalities and millions more to landowners for unpaid surface leases.

Does Alberta Premier Jason Kenney arrest the offending white collar criminals and charge them with breaking civil contracts? No. He actively excuses their behaviour.

So there is one rule of law in Canada for insolvent resource extractors, and another law for First Nations, rural municipalities and landowners.

Fortunately, the Wet’suwet’en respect laws that are thousands of years old.

They plan on upholding them.

So should we. SOURCE

RELATED:

Here is how you can take action in solidarity with land defenders on Wet’suwet’en territories:

Here is how you can take action in solidarity with land defenders on Wet’suwet’en territories:

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/politics/federal/2020/03/03/by-offering-to-recognize-wetsuweten-land-rights-ottawa-is-changing-the-way-canada-is-governed-heres-how/wet_suwet_en.jpg)

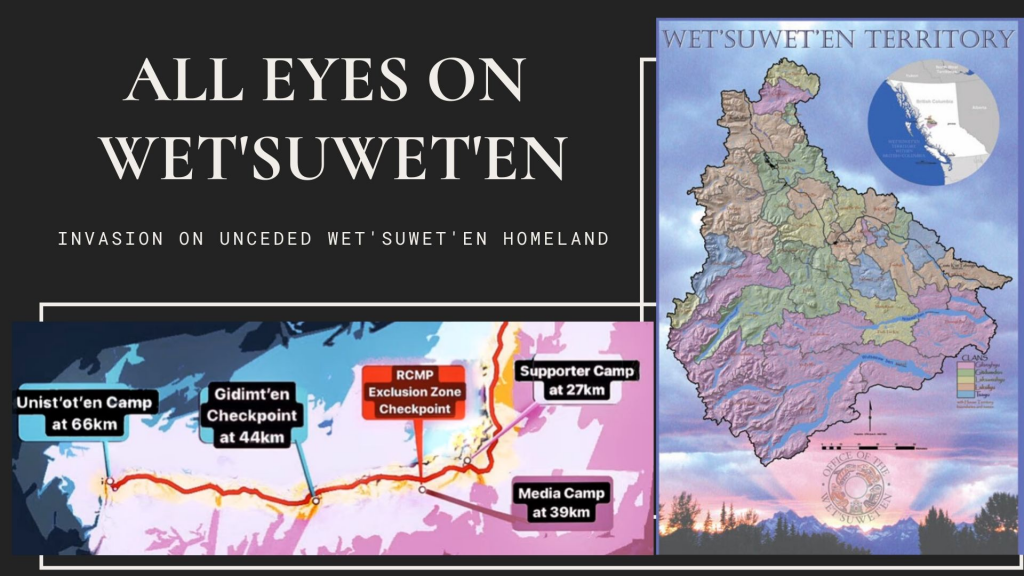

All eyes are watching as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) began their invasion on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory. We wanted to provide the map above along with a brief update from our Wet’suwet’en relatives so you can better understand the lay of the land in the fight against TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink pipeline being forced on the homelands of the Wet’suwet’en. Keep scrolling after updates for ways to take action.

All eyes are watching as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) began their invasion on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory. We wanted to provide the map above along with a brief update from our Wet’suwet’en relatives so you can better understand the lay of the land in the fight against TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink pipeline being forced on the homelands of the Wet’suwet’en. Keep scrolling after updates for ways to take action.

Here is how you can take action in solidarity with land defenders on Wet’suwet’en territories:

Here is how you can take action in solidarity with land defenders on Wet’suwet’en territories: