Our politics likely would be more stable, our economy more diversified.

An artist’s rendition of the proposed Woodfibre LNG plant near Squamish, one of 20 such projects once floated, but either cancelled or yet to be built.

Weeks of national rail blockades, Indigenous relations in tatters, and an emergency agreement between Ottawa and Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs. So what has been resolved?

Not much apparently. The B.C. government made it clear that it intends to push ahead with the contentious natural gas pipeline and the same route opposed by Wet’suwet’en Hereditary leadership.

How did we get in this mess and how do we get out?

As car wrecks go, this was as slow-motion as they come, political failures decades in the making. The same basic choices presented themselves to one political leader after another. Repeatedly they chose wrong or dithered.

Had they not, today’s government could enjoy stable and just relations with First Nations, partnering in a 21st-century economy that’s more clean and diversified. Instead we are mired in the consequences come home to roost.

The needless debacle of a RCMP intrusion onto Wet’suwet’en Traditional Territory is a result of successive governments failing to resolve outstanding title claims, which in the case of the Wet’suwet’en predate their 1985 court challenge to the B.C. government. This case eventually resulted in the landmark Delgamuukw decision from the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997 articulating the nascent principle in Canadian law of Aboriginal title.

What should have happened then was the hard and necessary work on the part of elected governments to negotiate settlements with individual First Nations, consistent with direction provided by the courts.

Twenty-three years later, pitiful progress has been made. The province has treaties with only three B.C. First Nations. Fifty-seven others that signed up with the B.C. Treaty Commission process are either still laboring at the table or “not currently negotiating” — including the Wet’suwet’en. There is no free lunch as the free-marketers say and the consequences of failing to resolve title issues were on obvious display at railway crossings across the country.

The foolish bet on LNG

True, to have wagered serious provincial resources on resolving complex treaty deals would have meant a bold roll of the dice 20 years ago. But it’s not as if B.C.’s government hasn’t instead bet huge on a play that today shows little prospect of ever paying off.

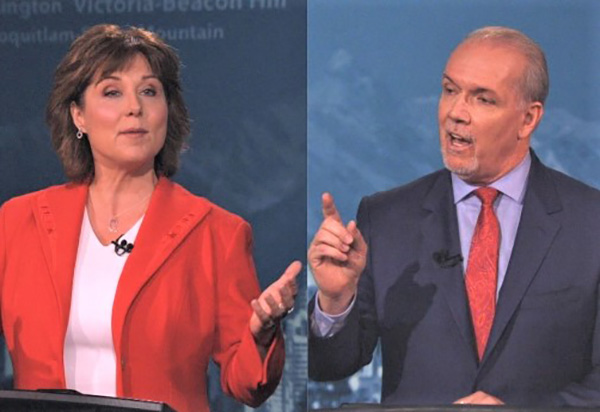

Seven years ago then-premier Christy Clark won election while misleading voters about the supposed riches liquefied natural gas would bring B.C. Even as she promised that by 2017 at least three LNG plants would be generating a $100-billion savings fund, erasing all debt and employing tens of thousands of people, experts declared that to be a fantasy.

By three years ago, methane prices had collapsed 75 per cent due to a worldwide glut and Australia’s LNG industry was bleeding losses.

Today, bizarrely, B.C.’s government continues to aggressively scale up natural gas extraction on unceded lands at the very moment in history such contentious pipeline projects make the least economic sense.

Natural gas prices around the world are tanking. Natural gas royalties in B.C. have shrunk to a minuscule portion of provincial government revenue while gas production — and emissions — have ballooned.

In the last ten years provincial gas production has increased 45 per cent while public revenues collapsed by over 90 per cent. With more than $380 million in provincial subsidies, the net return to taxpayers from gas production last year was only $153 million — less than 0.25 percent of Crown revenues. This supposed boom sector now provides the B.C. treasury one quarter as much money as taxing cigarettes.

According to B.C. government figures, the oil and gas sector directly and indirectly employed 12,600 people in 2019, or 0.49 percent of the provincial workforce — about the same number of people employed as couriers. Meanwhile reported emissions from well sites and pipelines now exceed that of all personal vehicles on the road in the province.

If we also include eventual emissions from burning the 52 billion cubic metres of natural gas produced in B.C. in 2017, the atmospheric burden amounts to more than 170 per cent of the entire B.C. economy.

Methane is over 20 times more powerful than CO2 in heating the atmosphere so limiting leaks over the vast and remote network of fracking facilities and pipelines is critical for fighting the climate emergency. However, peer reviewed research based on the first and only independent field sampling of well sites in northern B.C. found official estimates of fugitive methane from this supposed “green” energy are two-and-a-half times higher than reported by industry and the B.C. government.

Lead or get out of the way

The two most pressing issues facing the Canadian resource sector are honourably resolving issues of Aboriginal Title, and providing credible and predictable policies to address the climate crisis. However, various provincial governments seem to be still pretending that these imperatives do not exist.

Apart from an abysmal economic case, the CEO of Teck Resources made it clear that the absence of consistent public policy on climate change made their $20.6 billion Frontier bitumen mine project untenable. While Alberta Premier Jason Kenney sees political advantage in endless fights with Ottawa, industry instead seeks certainty. Most major fossil fuel companies have in fact been calling for predictable carbon pricing for years.

And finally now, after the Teck withdrawal and amidst the blockade crisis, Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland has decided, “What I think we need to do now is have a very urgent, very serious conversation between the federal government, the provincial government, the oil sector and indeed, the whole country….”

Here in B.C., the supposed imperative of natural gas extraction is blowing both our climate goals and efforts towards Indigenous reconciliation out of the water. It is long overdue to begin an honest conversation with the B.C. public about this planet-killing sunset sector.

The $10.7 billion Site C dam was approved largely in service of a long-hyped LNG boom that so far has only resulted in one single project under construction that is years from completion.

A world awash in cheap natural gas and the U.S. fracking industry will keep North American prices close to historic lows for the foreseeable future.

Much of our provincial production, meanwhile, is sold in Alberta to extract bitumen — itself a dying industry. LNG exports from Kitimat to mythically lucrative Asian markets are at least five years away — likely too late to secure global market share.

Vast amounts of monetary and political capital have been squandered on this boondoggle. When will we have the political courage to cut our losses and move on? Apparently not yet.

Likewise, there seems no likelihood of Jason Kenney’s government having an honest conversation about the future of the fossil fuel sector with Alberta’s voters. Even as private capital flees the sinking sector, he plans to throw scarce public money and pension funds at a doomed industry.

Why? Because it easier than admitting that years of overheated rhetoric to the contrary was simply untrue. Ripping up carbon pricing and picking fights with rating agencies only drives away what little investment might be interested in Alberta’s oil patch, but apparently the show must go on.

First Nations and their supporters have again reminded provincial and federal governments that resource extraction without respecting Indigenous rights is no longer acceptable. Markets have made it clear that the days of easy money thrown at fossil fuel megaprojects have also gone by the wayside, especially in the absence of credible carbon pricing.

It is the job of elected governments to provide leadership and certainty on the pressing issues of the day. Judging by the smoldering situation with First Nations in Canada and the jittery mood of investors in the resource sector, our leaders need to do better. Much better. ![]() SOURCE

SOURCE

RELATED:

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2020/02/29/enforcers-of-the-colonizers-wetsuweten-crisis-casts-spotlight-on-long-difficult-history-between-rcmp-and-indigenous-canadians/north_west_mounted_police.jpg)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2020/02/29/enforcers-of-the-colonizers-wetsuweten-crisis-casts-spotlight-on-long-difficult-history-between-rcmp-and-indigenous-canadians/blockade.jpg)