The billions attracted by tax havens do harm to sending and receiving nations alike

Until the 2008 financial crisis, tax havens were generally seen as exotic sideshows to the global economy, Caribbean islands or Alpine financial fortresses frequented by celebrities, gangsters, and wealthy aristocrats. Since then, the world has woken up to two sobering facts: first, the phenomenon is far bigger and more central to the global economy than nearly anyone had imagined; and second, the biggest havens aren’t where we thought they were.

Tax havens collectively cost governments between $500 billion and $600 billion a year in lost corporate tax revenue, depending on the estimate (Crivelli, de Mooij, and Keen 2015; Cobham and Janský 2018), through legal and not-so-legal means. Of that lost revenue, low-income economies account for some $200 billion—a larger hit as a percentage of GDP than advanced economies and more than the $150 billion or so they receive each year in foreign development assistance. American Fortune 500 companies alone held an estimated $2.6 trillion offshore in 2017, though a small portion of that has been repatriated following US tax reforms in 2018.

Corporations aren’t the only beneficiaries. Individuals have stashed $8.7 trillion in tax havens, estimates Gabriel Zucman (2017), an economist at the University of California at Berkeley. Economist and lawyer James S. Henry’s (2016) more comprehensive estimates yield an astonishing total of up to $36 trillion. Both, assuming very different rates of return, put global individual income tax losses at around $200 billion a year, which must be added to the corporate total.

These highly uncertain estimates vary widely because of financial secrecy and patchy official data and because there’s no generally accepted definition of a tax haven. Mine boils down to two words: “escape” and “elsewhere.” To escape rules you don’t like, you take your money elsewhere, offshore, across borders. I prefer such a broad definition because these havens affect far more than tax: they provide an escape route from financial regulations, disclosure, criminal liability, and more. Because the main corporate users of tax havens are large financial institutions and other multinationals, the system tilts the playing field against small and medium enterprises, boosting monopolization.

Political damage, while unquantifiable, must be added to the charge sheet: most centrally, tax havens provide hiding places for the illicit activities of elites who use them, at the expense of the less powerful majority. Tax havens defend themselves as “tax neutral” conduits helping international finance and investment flow smoothly. But while the benefits for the private players involved are evident, the same may not be true for the world as a whole; it is now widely accepted that in addition to tax losses, allowing capital to flow freely across borders carries risks, including the danger of financial instability in emerging market economies.

As a general rule, the wealthier the individual and the larger the multinational corporation—some have hundreds of subsidiaries offshore—the more deeply they are embedded in the offshore system and the more vigorously they defend it. Powerful governments also have a stake; most major havens are located in advanced economies or their territories. The Tax Justice Network’s Corporate Tax Haven Index ranks the top three as the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands—all British overseas territories. The organization’s Financial Secrecy Index ranks Switzerland, the United States, and the Cayman Islands as the top three jurisdictions for private wealth.

To grasp why rich jurisdictions top the lists, ponder how many rich Nigerians might stash secret assets in Geneva or London—then consider how many rich Swiss or Britons would hide assets in Lagos. Offshore capital tends to drain from poor countries to rich ones.

And the offshore system is growing. When one jurisdiction crafts a new tax loophole or secrecy facility that successfully attracts mobile money, others copy or outdo it in a race to the bottom. That has contributed to a dramatic decline in average corporate tax rates, which have decreased by half, from 49 percent in 1985 to 24 percent today. For US multinationals, corporate profit shifting into tax havens has risen from an estimated 5 percent to 10 percent of gross profits in the 1990s to about 25 to 30 percent today (Cobham and Janský 2017).

The principles of the international corporate tax system were laid down under the League of Nations almost a century ago. They treat multinational enterprises as loosely connected “separate entities.” This is a fiction: multinationals in fact draw great strength from their unitary nature, reaping market power and economies of scale. If the whole is worth more than the sum of its (geographically diverse) parts, which countries get to tax that extra value? It is rarely lower-income countries, since the system tends to give preference to the place where multinationals have their headquarters, usually rich countries.

What is more, multinationals can manipulate the so-called transfer prices of transactions between these affiliates to shift profits from high- to low-tax jurisdictions. For example, a firm’s affiliate may hold a patent in a low-tax haven and charge exorbitant brand royalties to affiliates in high-tax countries, thus maximizing profits in the low-tax jurisdiction. In theory, transfer prices are meant to reflect market prices that would prevail in arm’s length transactions between two unrelated parties. But such prices often cannot readily be established: try valuing a unique widget for a jet engine that isn’t sold on the open market, or a drug patent. In practice, the value is often what the company’s accountants say it is.

The main alternative to “arm’s length, separate entity” is something called “unitary tax with formulary apportionment.” This system considers a multinational to be a single entity and apportions profits geographically according to a formula reflecting real economic activity, which could be a mix of sales, employment, and tangible assets. In theory, this method cuts out tax havens: if a firm has a one-person office in Bermuda, the formula allocates a minuscule portion of its global profits there, so it hardly matters whether Bermuda taxes its portion at a zero rate. In practice, this system also suffers technical difficulties, and the choice of formula is highly political—but it is simpler, fairer, and more rational than the current system.

Indeed, many US states, Canadian provinces, and Swiss cantons have for some time used limited versions of the system for subnational taxes, even though it is not yet used internationally. A move is already underway to require multinationals to break down and even publish financial and accounting information on a country-by-country basis, which could provide relevant data for an international allocation formula. Many other incremental stepping-stones toward the alternative are possible, so change can be evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

Until a decade or so ago, there were few political brakes on the expansion of tax havens. After the 2008 crisis, however, governments came under pressure to close large budget deficits and to placate voters furious about taxpayer-funded bank bailouts, widening inequality, and the ability of multinationals and the wealthy to escape tax. The Panama Papers and Luxembourg Leaks revealed the use of tax havens for often nefarious purposes and reinforced the pressure to do something. So the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the rich-country group that is the main standard-setter for international tax matters, launched two big projects.

One is the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), a regime to exchange financial information automatically across borders so as to help tax authorities track the offshore holdings of their taxpayers. But the CRS contains many loopholes; for example, it allows people with the right passport to claim residence in a tax haven, rather than in the country where they live. The United States constitutes an even bigger, geographic loophole: under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, it collects information from overseas on its own taxpayers, but it shares little information the other way, so nonresidents can hold assets in the country in conditions of great secrecy, making the United States a major tax haven.

Still, the CRS brought some results. The OECD estimated in July 2019 that 90 countries had shared information on 47 million accounts worth €4.9 trillion; that bank deposits in tax havens had been reduced by 20 to 25 percent; and that voluntary disclosures ahead of implementation had generated €95 billion in additional tax revenue for members of the OECD and the Group of 20, which includes major emerging market economies.

The other big initiative was the base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) project, aimed at multinational corporations. This was the OECD’s effort to “realign taxation with economic substance” without disrupting the long-held international consensus supporting the arm’s length principle, which was bolstered by tax-escaping multinationals and their allies. While BEPS did improve transparency for multinationals, it was ultimately seen as something of a failure by the OECD, especially for the digitalized economy.

The United States also belatedly recognized that, with a consumption-heavy economy, it made sense to shift taxing rights toward the place where sales occur. And emerging market economies, including Colombia, Ghana, and India, which gained more clout starting in 2016, have pushed for new approaches. The OECD began considering sales-only formulas, but some lower-income countries favor a formula that includes employees and tangible assets, which would give them greater taxing rights. These shifts away from arm’s length orthodoxy represent a step toward tax campaigners’ demands for formula apportionment.

In January 2019 the dam began to break. For the first time, the OECD conceded publicly a need for “solutions that go beyond the arm’s length principle.” In March, Christine Lagarde, then managing director of the IMF, called the method “outdated” and “especially harmful to low-income countries.” She urged a “fundamental rethink” with moves toward formula-based approaches to allocating income. In May, the OECD published a “road map” proposing reforms based on two pillars: first, determining where tax should be paid and on what basis, and what portion of profits should be taxed on that basis; and second, getting multinationals to pay a minimum level of tax. Professor Reuven Avi-Yonah, of the University of Michigan Law School, said the plan was “extraordinarily radical” and would have been “almost inconceivable” even five years ago.

We are now at the start of the most significant period of change to the international corporate tax system in a century. Progress will hinge on power struggles: between countries, rich and poor, and within countries, between ordinary taxpayers and those that profit from the current system. But radical change is feasible. The Tax Justice Network, which I have worked with, now sees its four core demands, initially dismissed as utopian, gaining global traction: automatic exchange of financial information across borders, public registers of beneficial ownership of financial assets, country-by-country reporting, and now unitary tax with formula apportionment.

But corporate tax is just a start. To understand the broader issues, we must consider the forces that make the offshore system tick. Switzerland’s example is illustrative. In past decades, politicians in Germany, the United States, and elsewhere have clashed with Switzerland over banking secrecy, with little success. In 2008, however, after discovering that Swiss bankers had helped US clients evade tax, the Department of Justice took a different tack: it targeted not the country, but its bankers and banks. In response, the embattled private players became major lobbyists for reform, and Switzerland soon made major concessions on banking secrecy for the first time. The lesson: any effective international response must include strong sanctions against the private enablers, including accountants and lawyers—especially when they facilitate criminal activity such as tax evasion.

On a deeper level, consider this. The engine of the offshore system is competition among jurisdictions to provide the best ways to avoid taxes, disclosure, and financial regulation. Traditionally, such a race to the bottom is framed as a collective action problem requiring collaborative, multilateral solutions. But cooperative approaches have flaws. Some jurisdictions feel inclined to cheat as they seek to attract mobile capital, so collective action can be like herding squirrels on a trampoline. Moreover, it is tough to mobilize voters in support of complex cross-border collaboration, especially when the goal is to help foreigners or low-income countries.

There is a radically different, more powerful, approach. The relevant question is, Do the financial flows attracted by tax havens help the receiving countries? They certainly help interest groups there—typically in the banking, accounting, legal, and real estate professions—but do they benefit the jurisdiction as a whole?

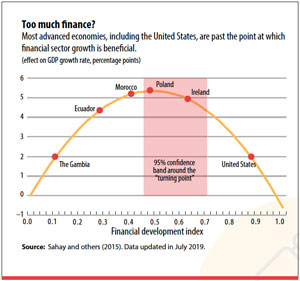

A new and growing strand of research by the IMF, the Bank for International Settlements, and others suggests that the answer is no. This “too much finance” literature argues that financial sector growth is beneficial up to an optimal point, after which it starts to harm economic growth (see chart, previous page). Most advanced economies, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and other major tax havens, passed that point long ago. For them, shrinking the financial sector to remove harmful financial activities should boost prosperity.

Alongside this research, John Christensen, a former economic advisor to the British tax haven Jersey, and I have developed the concept of a finance curse, which afflicts jurisdictions with an oversize financial sector and is analogous to the resource curse that vexes some countries dependent on commodities such as oil. This “paradox of poverty in the midst of plenty” has multiple causes: a brain drain of skilled people from government, industry, and civil society into the high-paying dominant sector; rising and growth-sapping inequality between the dominant and the other sectors; an increase in local prices that renders other tradables sectors less competitive with imports; recurrent booms and busts in prices of commodities and financial assets; and an increase in rent seeking and loss of entrepreneurship at the expense of productive, wealth-creating activities as easy money flows in. Some scholars also decry “financialization,” or a shift from wealth-creating activities toward more predatory, wealth-extracting activities such as monopolization, too-big-to-fail banking, and the use of tax havens.

Financial flows seeking secrecy or fleeing corporate taxes seem likely to be exactly the kind that exacerbate the finance curse, worsening inequality, increasing vulnerability to crises, and dealing unquantifiable political damage as secrecy-shrouded capital infiltrates Western political systems. And as financial capital flows from poorer countries to rich-world tax havens, labor migration will follow.

As ever, more research is needed here. Yet it seems that for many economies hosting an offshore financial center is a lose-lose proposition: it not only transmits harm outward to other countries, but inward, to the host. Countries that recognize this danger can act unilaterally to rein in their offshore financial centers, simply stepping out of the race to the bottom and curbing tax haven activity while also improving their own citizens’ well-being. This is a powerful, winning formula. SOURCE

A natural gas well pad with numerous wells for fracking near Farmington, B.C. The LNG industry in British Columbia is the recipient of numerous tax breaks and exemptions. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

A natural gas well pad with numerous wells for fracking near Farmington, B.C. The LNG industry in British Columbia is the recipient of numerous tax breaks and exemptions. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited Victoria in April of 2018 to reiterate the federal government’s support for the Trans Mountain pipeline and commitment to the Oceans Protection Plan. Photo: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited Victoria in April of 2018 to reiterate the federal government’s support for the Trans Mountain pipeline and commitment to the Oceans Protection Plan. Photo: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal