Like major contagions throughout history, the new coronavirus causes fear as well as illness. The remedy for both, it turns out, is the same

ILLUSTRATION BY SÉBASTIEN THIBAULT

BY KEVIN PATTERSON

TO BE ALIVE is to be afraid; anxiety is the spirit of this age and, substantially, of all ages. However good things have gotten, at least for those of us in Canada—however low crime and unemployment rates have become, however much war deaths have declined, life expectancy has grown, or HIV, cancer, and age-adjusted heart disease death rates have shrunk—disquiet claws at us. Financiers may advise that what they call the downside risk—the potential for loss in the worst cases—is limited, but at an existential level, we know better. Everything could just go all to hell, no matter how shiny things look. You don’t need to be a wigged-out prepper in the woods to suspect it.

Things have always gone all to hell. Over 4,000 years ago, climate change came to Mesopotamia, causing drought and a subsequent famine so severe that the world’s first empire, Akkad, simply ceased to be. Farmers abandoned their crops and many scribes just stopped writing. For archaeologists, for the next 300 years: near silence.

This is from The Curse of Akkad, written around the time of the silencing:

Those who lay down on the roof, died on the roof; those who lay down in the house were not buried. People were flailing at themselves from hunger. By the Ki-ur, Enlil’s great place, dogs were packed together in the silent streets; if two men walked there they would be devoured by them, and if three men walked there they would be devoured by them.

In the third century, the Three Kingdoms war shattered China. The An Lushan Rebellion, five centuries later, shattered it again. Millions died in each of: the Mongol conquests, the nineteenth century’s Taiping Rebellion, colonialism in the Americas, the Thirty Years’ War in Europe—and, of course, the World Wars, which killed, conservatively, over 110 million.

Famine and war routinely bring civilizations low, but though he trots closely beside those two, the horseman who carries off the most has always been pestilence. The Roman Empire’s Justinian Plague, which was perhaps history’s first known pandemic, is thought to have killed millions in the sixth century and may have further stressed the weakening imperium. Procopius writes contemporaneously that death rates in Constantinople were as high as 10,000 per day:

And many perished through lack of any man to care for them, for they were either overcome by hunger, or threw themselves down from a height. And in those cases where neither coma nor delirium came on, the bubonic swelling became mortified and the sufferer, no longer able to endure the pain, died.

This was humanity’s first catastrophic involvement with Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that would resurface again during the Black Death, killing 30 to 60 percent of the population of medieval Europe. Western Europe’s population would not reach what it had been in the 1340s again until the beginning of the sixteenth century. In subsequent centuries, cholera also swept the urbanized world—crowding being a powerful accelerant for non–vector borne (that is, not insect- or snail-spread) infection. (Paleolithic peoples saw no sustained human-to-human infections; their numbers were too small to keep up chains of transmission.) What John Bunyan called the “captain of all these men of death,” tuberculosis, has been with us for at least 9,000 years, since the Neolithic period, and has killed more than a billion humans in the last 200 years alone. It was responsible for 25 percent of all deaths in Europe between the 1600s and the 1800s. It remains the most lethal infection worldwide, killing about 1.5 million people a year, and currently infects one-third of living humans.

Those infections are bacterial, but history’s worst pandemic was caused by a virus that swept the world only a long lifetime ago: the misnamed “Spanish” flu of 1918–1920 was a strain of H1N1 influenza of unknown origin (any place where pigs and chickens and people live is a candidate). That illness was often complicated by a supervening bacterial pneumonia, for which there were then no antibiotics, and it spread around the world over the course of two years, ultimately killing 20 to 50 million. It killed, on average, 2.5 percent of the people it infected, but certain communities were hit much harder: about 7 percent of Iranians died, a third of Inuit in Labrador, and 20 percent of the Samoan population.

In The Great Influenza, historian John M. Barry quotes an American Red Cross worker: “Not one of the neighbors would come in and help. I . . . telephoned the woman’s sister. She came and tapped on the window, but refused to talk to me until she had gotten a safe distance away.” Barry continues: “In Perry County, Kentucky, the Red Cross chapter chairman begged for help, pleaded that there were ‘hundreds of cases . . . [of] people starving to death not from lack of food but because the well were panic stricken and would not go near the sick.’”

Contagion may be a leading cause of death, but the worst thing it ever does is prompt us to recoil from one another—much the greater injury: to our health, to our communities, to whatever it is that stands in the way of this slouching beast.

This January and February, things started looking like they could again go all to hell. (They may yet.) Wuhan, in the province of Hubei, China, is a transportation hub of 11 million built where the Yangtze and Huan Rivers meet. In December, patients began presenting, in steadily increasing numbers, with symptoms and clinical findings suggestive of viral pneumonia. (Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs; it may be caused by viruses, bacteria, or fungi.) Tests for known pathogens capable of causing such an illness came back negative. This raised the question of whether a novel pathogen—an infectious agent not previously known to affect humans—had emerged.

Novel pathogens inspire a particularly pointed sort of anxiety among doctors. Many familiar pathogens are lethal on a broad scale—influenza caused over 34,000 deaths in the US in 2018/19, for instance—but their behaviour is known and tends to be consistent. Seasonal influenza, for example, is active in the northern hemisphere beginning in November; its spread slows dramatically by late March. It is monitored carefully and understood well enough that vaccines may be prepared that are usually effective at reducing disease incidence and severity. We know how to contain this virus, we know which patients will be the most vulnerable to it, and we know, within an order of magnitude, how many will die. The ceiling on that number matters. While the best-case scenario for influenza each year includes many deaths, we also have an idea of what the worst-case scenario is. The downside risk is not infinite.

With novel pathogens, this is not true. The worst-case scenario is undefined. Novel pathogens are not inevitably virulent or necessarily prone to become epidemic, but some of them do prove to be catastrophic—and doctors don’t know, when one emerges, what course it’s going to take.

The number of ill in Wuhan grew quickly, as did the number of medical researchers paying attention. On December 31, China notified the World Health Organization (WHO) that it was seeing an outbreak of pneumonia due to an unknown agent. By January 7, Chinese virologists had sequenced the genetic structure of this new virus—which has been dubbed SARS-CoV-2 (the illness that it causes is called COVID-19)—posting it online so that researchers around the world could access it. A few days later, an apparent connection to the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market, in Wuhan, was reported to the WHO, and the market was quickly ordered to close. On March 11, following growing transmission in countries around the world, the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, which it defines as “the worldwide spread of a new disease.”

The virus was found to be part of the family of Coronaviridae, or coronaviruses: a large group of viruses that are so named because, when examined with an electron microscope, they appear studded with projections that suggest a crown. Benign instances of coronaviruses cause up to a third of common colds. A more alarming example is the SARS virus, which leapt from an unknown agent (likely bats) to civet cats and caused a multinational outbreak, killing about 10 percent of the 8,000 people it infected, and which hit Toronto, where forty-four people died of the illness. Another coronavirus leapt from camels to humans in 2012 or earlier and causes a type of pneumonia called MERS, or Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, which persists in Saudi Arabia. These new coronaviruses are zoonotic: they originated in animal populations and were then transmitted to humans. Researchers concluded early on that SARS-CoV-2’s leap to humans had occurred quite recently, likely sometime last November.

The story of this pandemic is, in many ways, a story about speed. HIV circulated among humans for about six decades before it was noticed. The quickness with which science has identified this new infection and defined the genetic nature of the virus causing it is unprecedented, but this is matched by the virus itself: the rapidity with which it was observed to leap to humans and the rate at which it was seen to disseminate among us has almost no parallel in modern medicine.

Everything about this story is fast: the science, the virus, and the almost instantaneous popular fascination with and fear of unfolding events—spread by social media but also by traditional journalism and a public sensitized by Ebola and 2009 H1N1. The spirit of our age anticipates disaster when once it anticipated flying cars. For a time after 9/11, every loud noise was a bomb and every brown man a bomber. The disasters of our time have been mostly human caused (or anthropogenic, as the climatologists put it). Given human obduracy, this is less reassuring than it might be.

The Chinese government’s information management around the COVID-19 outbreak worsened our general unease. China has been more forthcoming than it was with the 2003 SARS outbreak, but even so, it has not been broadly transparent. Frustration over this among the citizenry crystallized over the treatment of Li Wenliang, a thirty-four-year-old ophthalmologist in Wuhan who alerted his former medical-school classmates to the outbreak, on December 30, over WeChat, the Chinese messaging and social media platform. After being summoned for questioning by police and signing a statement that his warning had “disturbed [the] social order,” he was released—only to come down with COVID-19 himself, dying of it on February 7. The indignation and anger on Chinese social media was uncharacteristically plain-spoken.

The early clampdown on information had many repercussions. Echo Xie, a reporter for the South China Morning Post, travelled to Wuhan in the first weeks of the outbreak. As recently as late January, she told me, “a lot of people didn’t take it seriously. It’s been almost twenty days since the Wuhan health authorities first published information about the coronavirus, but some people still haven’t heard about it.” She went on to describe some of the people she had met:

A woman surnamed Xu, thirty-one, said her father, her brother-in-law, and a family friend had all developed severe pneumonia and breathing problems. Her father had caught a fever in early January, after a business trip to the southern region of Guangxi. He was treated for a common cold at first, but his condition kept worsening. He went to the hospital on January 12, where he was not formally admitted as the hospital had no beds left; he was instead put in an observation room—one that he shared with eleven other patients with different illnesses, with no partitions separating beds. An X-ray showed his lungs were infected, but at that time, he could still walk. On January 19, when he got another X-ray, three doctors told Xu that her father was in a very serious situation and there was a large area of shadow on his lungs. Still, he was kept in the same room as others, without quarantine facilities.

People were asking for help online when almost every hospital was full and no longer accepting any new patients. Yuan Yuhong, a professor in Wuhan, posted on WeChat: “Parents of my son-in-law were infected by the coronavirus and they were diagnosed, but now no hospital accepts them.”

SEVERE VIRAL pneumonias are a familiar problem to intensive care units all over the world, and the level of resources that must be devoted to the care of such patients is high, often straining existing health care structures even with the comparatively low numbers of such patients that are usual most years. ICU care is expensive, costing more than $1,500 per day, and maintaining surge capacity—the ability to respond to an abrupt increase in caseload—is correspondingly expensive. And so, little elasticity exists in most Western medical systems, including Canada’s.

The H1N1 influenza strain of 2009 (commonly referred to at the time as “swine flu”) is perhaps the most recent outbreak in Canada that can give a sense of what COVID-19 would be like if it spread here in earnest. Intensive care units were profoundly taxed with patients who had needs that were similar to those of the most serious COVID-19 cases. Supporting critically ill patients—those in multisystem organ failure—requires ventilator support, dialysis, and one-to-one or sometimes even two-to-one nursing staff. It takes only a few such cases to stretch an ICU and its staff, together with allied disciplines, such as respiratory therapists, to their limits, or past them.

In the intensive care unit where I work as a critical care physician, in Nanaimo, on Vancouver Island, we began seeing such patients in late December 2009; by January, we were consistently over capacity. Nanaimo is a medium-size city of just over 100,000, and the Nanaimo hospital has nine ICU beds—a little fewer than the national average of about 12.9 beds per 100,000 people. In such a setting, even a handful of extra patients requiring high-level care can put unsustainable pressure on the system. And it did. By March, the nurses, who had worked long overtime hours for months, were spent.

Those days had a frenetic quality to them that lingers in the memory of clinicians. Usually, the patients were admitted through the emergency room after several days of fever and coughing—familiar symptoms of influenza, which progresses just as COVID-19 progresses. When pneumonia supervenes, breathlessness is the most common indication that things are going badly. This is a consequence of inflammation in the lungs limiting their ability to transfer oxygen to the blood and to permit the exhalation of carbon dioxide.

With respiratory distress comes confusion and agitation; if that distress becomes severe, there may be a decision to sedate and intubate the patient—to pass a plastic tube into the trachea in order to force oxygen into the lungs and facilitate the removal of CO2. The tube is connected to a ventilator and the pressures and volumes of oxygen-enriched air are titrated to adequately support lung function without overdistending the lungs—a narrow window with patients so sick. People with severe pneumonia are often laid prone, on their fronts, in their beds, usually chemically paralyzed and sedated to the point of anaesthesia. Special intravenous catheters will have been placed by this point, leading to the large veins that drain into the heart, to facilitate the administration of powerful medicines to support blood pressure. Dialysis catheters may also be necessary if the kidneys are failing, and that, in turn, will usually be treated with continuous dialysis machines, requiring a dedicated nurse and the help of kidney doctors.

That process of stabilization and the initiation of life support systems will occupy a physician, a respiratory tech, and three or four nurses for one to three hours, when it goes well. Three such admissions would fill a day—in addition to the care required for other patients, with heart attacks and abdominal infections and injuries from car accidents, which do not go away during a pandemic—and still leave our ICU short a dialysis machine.

This is what clinicians know: a few dozen extra cases—each of which may require many weeks of care—in a winter can be overwhelming. It is impossible to even imagine how hundreds or thousands of such cases would be managed.

In retrospect, after 2009 H1N1—as well as after SARS and the other recent near misses, to say nothing of the fifteen-century history of pandemics—the surprising thing is how little was done subsequently to prepare for the next disastrous outbreak. There are not boxes full of spare ventilators in the basements of North American hospitals, ordered in volume once H1N1 subsided. There are not broadly understood and detailed plans for coping with the toll of caregiver infection, for housing and feeding the many new staff the medical and ICU wards would suddenly require; personal protective gear has not been stockpiled in anything like sufficient quantities—indeed, according to Tedros Ghebreyesus, director general of the WHO, worldwide supplies are already under severe strain.

AS MUCH AS the COVID-19 story is about speed, it is also about fear. Frightened people behave badly; contagion makes them recoil from one another. This serves the purposes of the horseman, distracting from important problems and their solutions and making marginalized people—some of whom seem often to be deemed culpable for epidemics—even more vulnerable. Plagues preferentially consume, whether directly or indirectly, the poor and powerless; it is a taste they have exhibited since Procopius.

As a barometer of fear and social dissolution in pandemics, othering has a long history; contagion has, for centuries, been associated with disparaged minorities. The Black Death certainly did not inaugurate anti-Semitism, but there is evidence that it propelled it to new depths. More than 200 Jewish communities were wiped out by pogroms justified by the libel that Jews were responsible for the plague in that they had poisoned local wells. There is a terrible account in Jakob von Königshofen’s history of Agimet of Geneva, a Jew who was “put to the torture a little” until he confessed to having poisoned wells in Venice, Calabria, and Apulia, among others. This became a narrative that accompanied the plague as it moved throughout Western Europe.

A similar othering effort was applied to gay and bisexual men when HIV was first recognized, attributing the HIV pandemic directly to sexual practices and indirectly to drug use (particularly amyl nitrate, or “poppers”) that lowered inhibitions—which is to say, to the queer “lifestyle.” Bathhouse culture was implicated—as if promiscuity were only the province of gay men—as was intercourse between men.

Alongside these noxious comments, a competing—and equally racist—account of COVID-19 began circulating. A paper—later retracted—was distributed prior to peer review arguing that SARS-CoV-2 had such “uncanny” genetic commonality with HIV that it was probably bioengineered, presumably by the Chinese, who have a microbiology lab located in the Wuhan Institute of Virology. This fringe theory (the genetic sequences in question aren’t just in common with HIV but with many other viruses) was repeatedly espoused by Tom Cotton, a Republican senator from Arkansas. (He later walked back the claim.)

Sinophobia has acted at a more local level as well. During the height of the 2003 SARS outbreak, business at Chinese restaurants in Toronto dropped by 40 to 80 percent. Restaurateurs in Chinatowns across Canada were seeing customers stay away before the epidemic had even arrived. And, in January, parents in a school board just north of Toronto signed a petition demanding that a student who had recently travelled to China not be admitted to school; it now has just over 10,000 signatures. “This has to stop. Stop eating wild animals and then infecting everyone around you. Stop the spread and quarantine yourselves or go back,” wrote one signatory.

THE MEASURE of a plague is the number of people it infects and how seriously it sickens them. The number of people it’s expected to infect multiplied by its mortality rate yields its prospective death toll. And this, naturally, is the question that draws the most attention: How bad is it going to get? How many are going to die? What are the numbers? People seek numbers in times of uncertainty because it feels like they have a solidity about them. A quantified subject is a tamed one, to some extent.

The R0, or the basic reproductive number, is a tool that allows epidemiologists to describe how contagious a pathogen is in a given circumstance. It is the average number of people who will in turn be infected by each new infection. If it is less than 1, the infection dwindles. More than 1, it spreads. Regular seasonal flu has an R0 of about 1.4; pandemic flu between 1.5 and 2, depending on the strain. Some early calculations estimated COVID-19’s R0 to be as high as 4, but as with the mortality rate, successive estimations moderated the result, and by mid-February, most experts estimated it at between 2 and 2.5. Which remains high compared to influenza but is hardly unprecedented. Measles, in unvaccinated and crowded populations, can be as high as 18.

Other numbers are needed to understand how fatal a pathogen is. A point made often, early in the course of COVID-19, was that its mortality rate is much lower than that of SARS (10 percent) or MERS (34 percent). Though it is too soon to pin down the mortality rate of COVID-19, current estimates put it at between 1 and 4 percent. (In Wuhan, where the health care system has clearly been profoundly stressed, it is at the higher end of that range. Elsewhere, the early numbers, at least, have been lower.) This follows known patterns: as a general rule, there is an inverse relationship between mortality and spread; COVID-19 has infected many more people than SARS or MERS and has a lower fatality rate.

Paradoxically, the lower virulence of SARS-CoV-2 makes it more dangerous. With SARS, people who were infected but not yet symptomatic were mostly not contagious. When they did fall ill, they often felt so unwell so quickly that they took to bed or went to the hospital—where they became very contagious. Many nurses were infected, but community spread was limited.

With SARS-CoV-2, it seems that many quite contagious infected people may feel well initially or indeed throughout their infection. Decreased virulence is bought at the price of increased contagiousness, and even if infected people are a quarter as likely to die, ten times as many people have been infected, and many more infections are yet to occur. The Spanish Flu’s fatality rate was under 2.5 percent; the WHO believes it killed about 50 million, though some other estimates go as high as 100 million. Seasonal influenza’s fatality rate is generally accepted to be about 0.1 percent—though it, too, is lethal, killing tens of thousands of North Americans every year as a consequence of how widespread it becomes every winter.

There are reasons for optimism and reasons for pessimism.

One point that needs more emphasis is that epidemics have diminished in much of the Global North for good reason. There has not been an uncontained and uncontainable epidemic on the scale of 1918 in over a century. This is only partly because of specific antibiotics, antiviral therapy (for viruses like HIV and hepatitis C), and vaccines. A large part of this is due to affluence and, to a qualified and recently diminishing degree, justice. The poor in the rich parts of the world no longer often die of hunger. For a majority, drinking water is cleaner. The crowding and misery of Dickensian London saw tuberculosis become the leading cause of death among adults; over the course of the twentieth century, that death toll fell 90 percent. Streptomycin, the first effective antituberculosis antibiotic, was made available in 1947, but there was a huge drop in infections prior to that due to improvements in quality of life. There had been some redistribution of wealth, and the very poorest were less poor than they had been. Tuberculosis in most of Canada is almost gone. But, in Nunavut, which has Canada’s highest poverty rate, the incidence was recently comparable to Somalia’s.

But the reasons for anxiety are compelling too. A vaccine is at least a year away. There is no drug with proven efficacy against the virus. As of this writing, the virus is present in more than 100 countries. There are nearly 8 billion humans on the planet; the next largest population of nondomesticated large mammals is the crabeater seal, around Antarctica: 15 million. We live, worldwide, mostly in cities and now in densities that make us profoundly vulnerable. As Michael Specter, writing presciently in The New Yorker about pandemics, has pointed out, few of us can completely isolate ourselves—and, in Wuhan, the lockdown cannot continue indefinitely. In other parts of the world, where the central government is less powerful, it could not even be initiated. People need food; people need medicine; people need one another.

Nothing important about us and our success as a species can be understood except by looking at our interdependencies. If many of us could not come to work—because of sickness, because of the need to care for loved ones, or because of mandated social-distancing—then the fabric of our society would begin to tear. Transportation networks would fail; airports would cease to operate. Human beings are ambivalent about their interdependence. To need others is to be vulnerable; when we’re under threat, vulnerability elicits fear.

Despite our hopes, and despite the unprecedented quarantine, COVID-19 was not contained in Wuhan as SARS, improbably, was contained and extirpated in Toronto and the other cities it broke out in. The Wuhan lockdown did slow the epidemic, however, and relieved the pressure on the city’s health care system, which was failing.

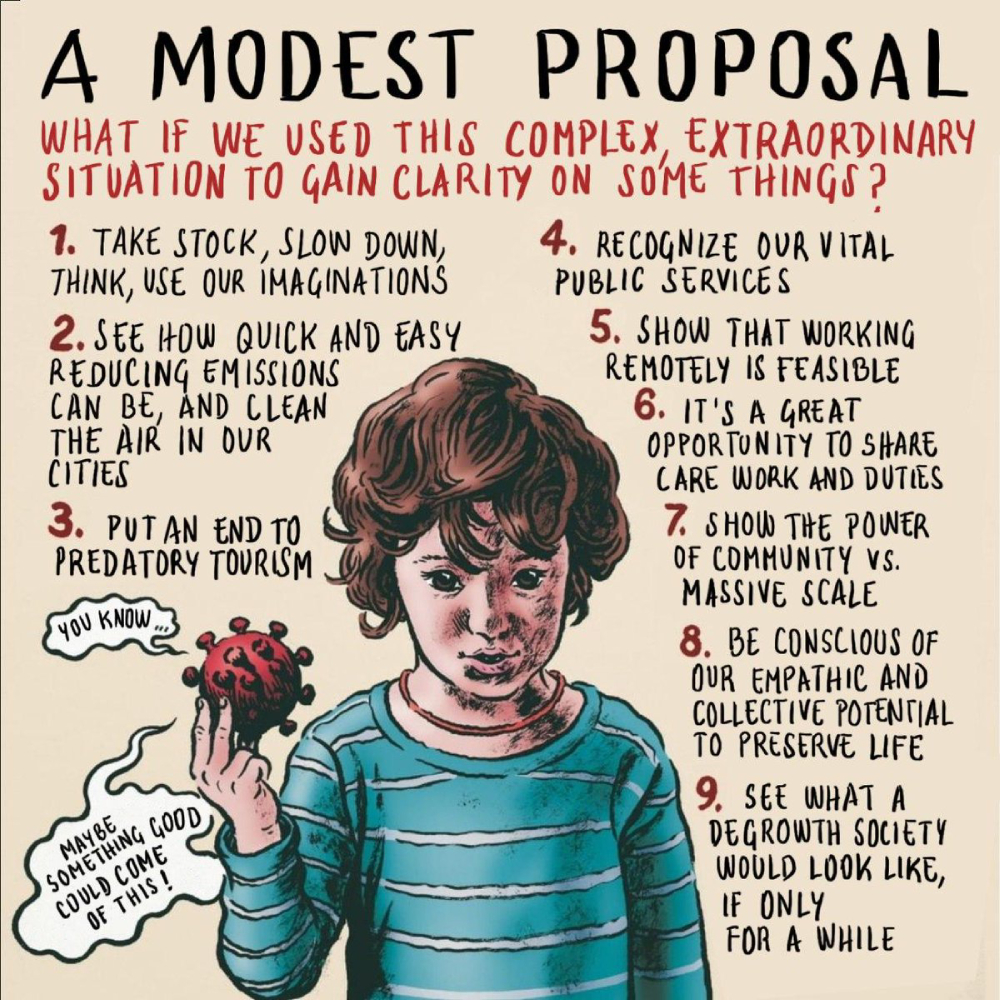

Now, the rest of us brace for a version of what the Chinese experienced. We must now contemplate how much we need one another. The instinct to recoil would be the worst possible response because doing so would ensure that the most vulnerable among us are consumed. And, in a pandemic, that injury would not be purely moral or social—though it would be those too. It would feed the contagion, overwhelm the hospitals, and increase the risk to the less vulnerable. Rarely is the argument for mutual devotion so easily made.

It might be that that this pandemic will turn out less severe than what is feared; it might be that the winter spike in Wuhan will not be replicated elsewhere. But, even if we contain this virus, there will be another. And this point, that some threats can be faced only collectively, will remain. We have to learn it. SOURCE

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/editorials/2020/03/19/coronavirus-shows-its-time-to-mend-the-safety-net/sr_covid19_031920_18.jpg)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/public_editor/2012/03/09/canadian_charter_of_rights_what_is_the_status_of_press_freedom_in_canada/charter.jpeg)