Employees of IESO oversee one of the electricity system’s control rooms. Photo courtesy of Independent Electricity System Operator

For almost a year, the operator of Ontario’s electricity system erroneously counted enough phantom demand to power a small city, causing prices to spike and hundreds of millions of dollars in extra charges to consumers, according to the provincial energy regulator.

The Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) also failed to tell anyone about the error once it noticed and fixed it.

The error likely added between $450 million and $560 million to hourly rates and other charges before it was fixed in April 2017, according to a report released this month by the Ontario Energy Board’s Market Surveillance Panel.

It did this by adding as much as 220 MW of “fictitious demand” to the market starting in May 2016, when the IESO started paying consumers who reduced their demand for power during peak periods. This involved the integration of small-scale embedded generation (largely made up of solar) into its wholesale model for the first time.

The mistake assumed maximum consumption at such sites without meters, and double-counted that consumption.

The OEB said the mistake particularly hurt exporters and some end-users, who did not benefit from a related reduction of a global adjustment rate applicable to other customers.

“The most direct impact of the increase in HOEP (Hourly Ontario Energy Price) was felt by Ontario consumers and exporters of electricity, who paid an artificially high HOEP, to the benefit of generators and importers,” the OEB said.

The mix-up did not result in an equivalent increase in total system costs, because changes to the HOEP are offset by inverse changes to a Global Adjustment rate, the OEB noted.

Peak time spikes

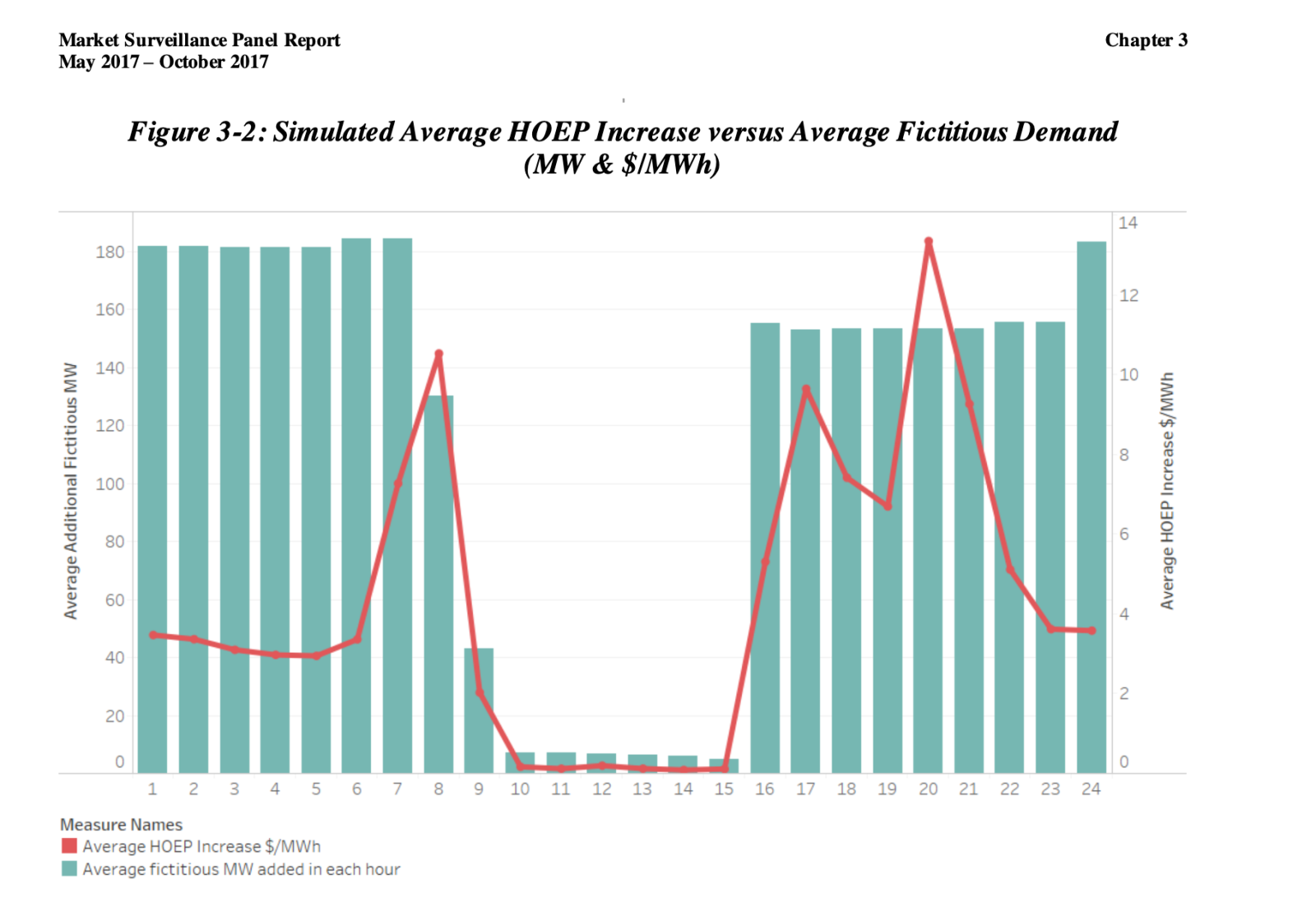

The OEB said that the fictitious demand “regularly inflated” the hourly price of energy and other costs calculated as a direct function of it.

For almost a year, Ontario’s electricity system operator @IESO_Tweets erroneously counted enough phantom demand to power a small city, causing price spikes and hundreds of millions in charges to consumers, @OntEnergyBoard says. @5thEstate reports.

It estimated the average increase to the HOEP was as much as $4.50/MWh, but that price spikes would have been much higher during busier times, such as the mid-morning and early evening.

“In times of tight supply, the addition of fictitious demand often had a dramatic inflationary impact on the HOEP,” the report said.

That meant on one summer evening in 2016 the hourly rate jumped to $1,619/MWh, it said, which was the fourth highest in the history of the Ontario wholesale electricity market.

“Additional demand is met by scheduling increasingly expensive supply, thus increasing the market price. In instances where supply is tight and the supply stack is steep, small increases in demand can cause significant increases in the market price.

The OEB questioned why, as of September this year, the IESO had failed to notify its customers or the broader public about the mistake and its effect on prices.

“It’s time for greater transparency on where electricity costs are really coming from,” said Sarah Buchanan, clean energy program manager at Environmental Defence.

“Ontario will be making big decisions in the coming years about whether to keep our electricity grid clean, or burn more fossil fuels to keep the lights on,” she added. “These decisions need to be informed by the best possible evidence, and that can’t happen if critical information is hidden.”

In a response to the OEB report on Monday, the IESO said its own initial analysis found that the error likely pushed wholesale electricity payments up by $225 million. That calculation assumed that the higher prices would have changed consumer behaviour, it said.

In response to questions, a spokesperson said residential and small commercial consumers would have saved $11 million in electricity costs over the 11-month period, while larger consumers would have paid an extra $14 million.

That is because residential and small commercial customers pay some costs via time-of-use rates, the IESO said, while larger customers pay them in a way that reflects their share of overall electricity use during the five highest demand hours of the year.

The IESO said it could not compensate those that had paid too much, given the complexity of the system, and that the modelling error did not have a significant impact on ratepayers.

While acknowledging the effects of the mistake would vary among its customers, the IESO said the net market impact was less than $10 million.

It said it would improve testing of its processes prior to deployment and agreed to publicly disclose errors that significantly affect the wholesale market in the future. SOURCE

Sunlight breaks through dark clouds shining on a wind farm in Wilhelmshaven, on the North Sea coast of Germany this month. (Mohssen Assanimoghaddam/The Associated Press)

Sunlight breaks through dark clouds shining on a wind farm in Wilhelmshaven, on the North Sea coast of Germany this month. (Mohssen Assanimoghaddam/The Associated Press)